Bailey Trela

Prophets in the Wilderness: On Utopian Dreaming in the American Midwest

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

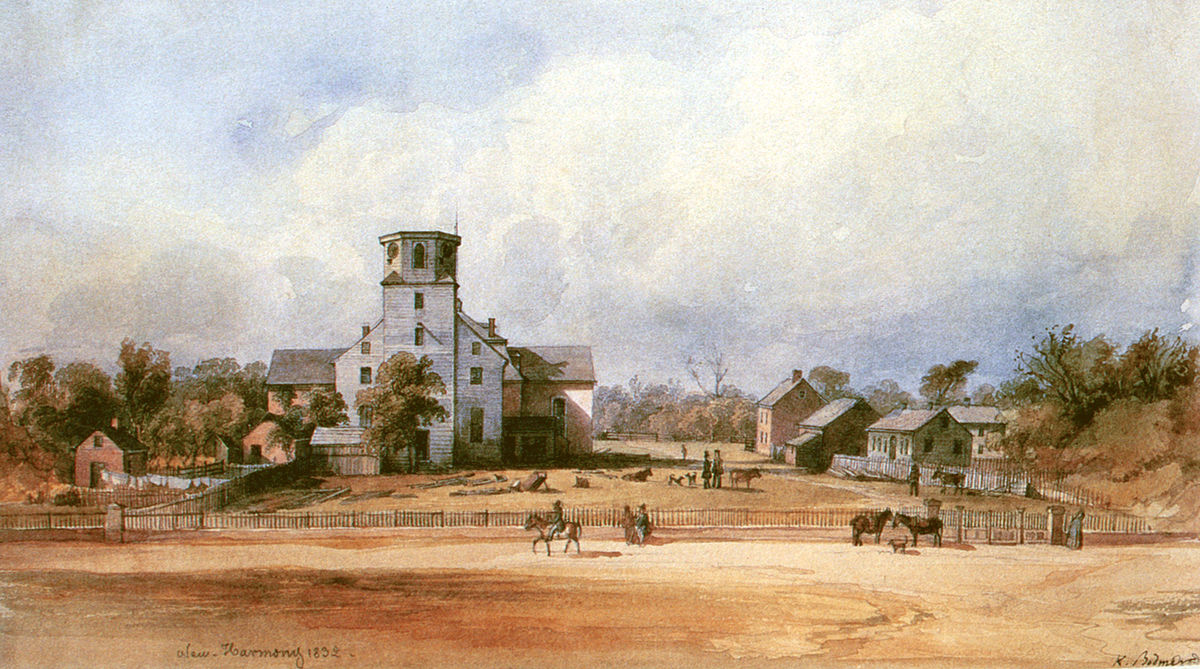

New Harmony, Karl Bodmer 1832

The labyrinth stood just north of Maple Hill Cemetery, the pleasantly incommodious hillside resting place where some two centuries’ worth of our town’s dead lie in shaded ranks. It was made of withered hedgerows and punctuated in its center with a crude stone hutch; we played tag in it, awkwardly, always forgetting as we started that it wasn’t a true maze, that the winding path was continuous, led only to the center.

There were other structures too, log cabins, wooden cottages, and grand brick buildings with gambrel roofs that stood empty and through the half-curtained windows of which, sitting on a friend’s shoulders, you could spy odd arrangements of period furniture—spindly rocking chairs and rough-looking three-legged stools. We visited these places on field trip after field trip, since the local school, which was shut down in 2012, rarely sprang for experiences farther afield.

There was a split, in the community, over how to think about these things and the past that had left them to us—or whether to think about it at all. They went unacknowledged, as far as I could tell, by the waitresses and farmers and maintenance workers who made up much of the population. The fact that our school’s sports teams bore the settlers’ demonym—the Mount Vernon Wildcats squaring off, bemusedly, against our mysteriously monikered Rappites, clad in blue and white—spoke to our habituation to the past, its ubiquity depriving it of any glamor.

Our teachers—some of them out of real interest, others simply because it was part of the curriculum—seemed to know the most. Mrs. Morrow, a solitaire-playing nicotine fiend who taught fourth grade, could be seen in a documentary feature that played in the town’s visitor center, casting seeds from her period apron (an early 19th century affair) against the rising sun. At school, when she clacked away at our desks with her artificial nails or left me or some other responsible-looking child in charge of the class while she took a smoke break, I’d think about the strange layering of her existence, the white bonnet I’d seen her wearing on the screen.

Our sixth grade teacher, Mr. Frasier, a short, stern presence with a mustache like a bulrush, would take us across town to the Wolf House, an ancient brick building inside of which a diorama of the town as it had existed 200 years before was lit up in a glass container like a terrarium. Looking at it, I had the unnerving feeling of seeing the past refleshed.

In the early 19th century, my hometown of New Harmony, Indiana was the site of two discrete attempts at utopian communal living. The first was spearheaded by the German Pietist preacher George Rapp, a millenarist convinced he would shortly present his followers at the gates of heaven. The second, the briefer of the two, was led by the British industrialist Robert Owen. Both projects were, in their own way, attempts at prophecy—Rapp thought Christ would return in a matter of years, while Owen saw his schematized town as the ideal community of the future, a way of eluding the manifest depredations of industrialization.

How did this history filter down to us in the present day? If anything, it settled into pre-existing divisions. We learned about the educational improvements and naturalist breakthroughs engendered by Owen’s presence in school, but by and large the town’s cultured class—the Mumfords, who ran the local concert series; the artisans (potters, painters, musicians) who’d settled there; the owners of the town’s various art galleries—were more enamored of the Rappites, or at least the mystical aura their one-time presence lent the town. For the majority of the town’s inhabitants, history was at once a practicality—drawing tourists and their pocketbooks to the tail-end of Indiana—and a vaguely exotic overlay, one that almost retroactively justified the music festivals and paint-offs and theater projects that otherwise would have seemed hopelessly out of place in this little town in the wilderness, whose population, for the past 200 years, has rarely been above 1,000 residents.

Movements in the Midwest

In the early and middle years of the 19th century, the Midwest was fertile ground for revolutionary communal endeavors. Octagon City, in Kansas, was built by vegetarians who lived in eight-sided houses; Bishop Hill Colony, in Illinois, served as a religious commune for Swedish immigrants; Oberlin Colony, in Ohio, existed for nearly a decade, founded on the principle of communally owned property. Fourier societies sprang up in Wisconsin and Ohio, as well as an unaffiliated Owenite community in Fruit Hills, Ohio. Typically small, these communities were often formed around a handful of immigrant families. Few of them lasted longer than a few years.

There are a number of reasons the Midwest became a hotbed of communalist activity. In a general sense, the religious liberty to be found in what were perceived as the unpeopled reaches of the fledgling territories—but which had, in reality, been forcibly depeopled—proved attractive both to homegrown visionaries and to international immigrants fleeing persecution in Europe. Beyond this, government policies after the War of 1812—when the push to expand the Union reached a fevered peak—gave generous terms to new settlers. The Homestead Act of 1862, for instance, divvied up great tracts of land into 160-acre plots, which would be sold to families at a steep discount provided they lived and worked on them for at least five years.

More specifically, the grid survey system established by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had originally set plot sizes at a level that encouraged corporate settlement, a policy that, as Phil Christman writes in Midwest Futures, helps to explain the preponderance of so many 19th-century attempts at communal living in the Midwest. “Large pools of money are characteristic of greedy capitalism,” he writes, but they’re also “sometimes characteristic of groups of fanatical idealists who, like the early Christians, hold all things in common.”

Harmonie on the Wabash

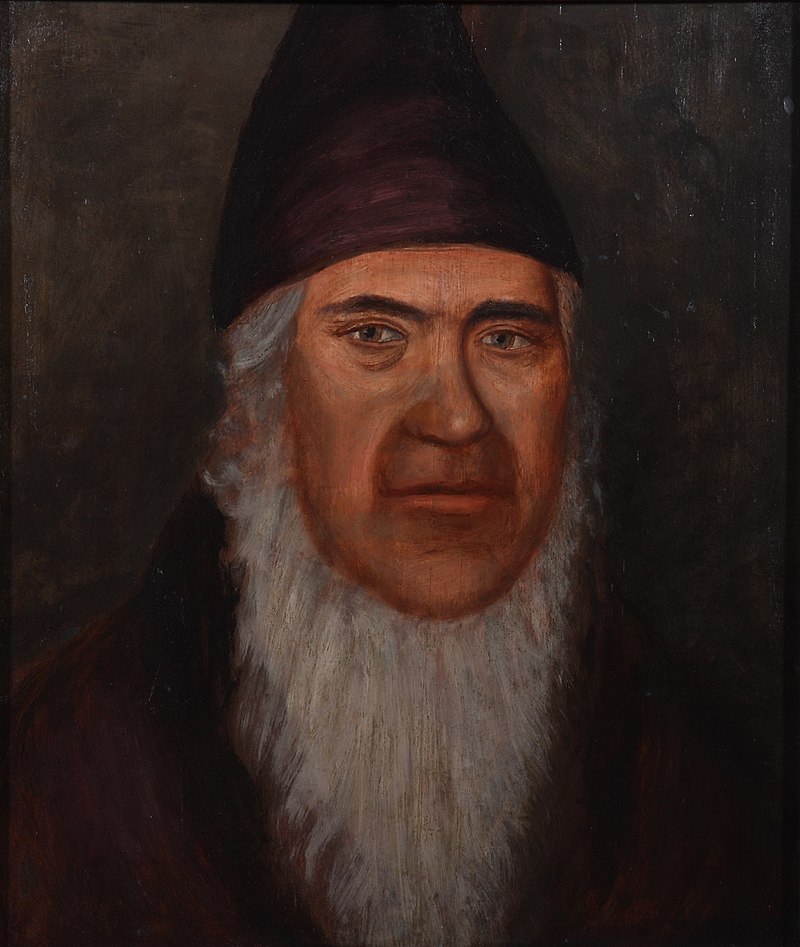

At the age of 30, George Rapp began to preach from the confines of his dark, narrow, high-gabled home in Iptingen, in southwestern Germany. With his strangely engorged features, including a lantern jaw and a stiff, white, gnome-like beard, Rapp was an earthy, rough-hewn orator, railing against the Lutheran church of his time in speeches that quickly drew large crowds—and, shortly thereafter, persecution.

Portrait of George Rapp, date unknown

Fleeing the country and setting up shop far away from probing eyes and minds soon became a priority as the fledgling troupe of Rappites was subjected to greater and greater harassment—their private meetings were shut down; they were threatened with expulsion and exile; they were fined for distilling brandy and sawing on a Sunday; their finances were aggressively interrogated; and Rapp himself was confined in a tower for two days.

Rapp’s heretical views were a confused mélange culled from his own self-directed studies, biblical exegeses, and readings of philosophers and theologians like Johann von Herder. By 1807 having relocated to Pennsylvania, the group had formally adopted the practice of celibacy. Rapp had become convinced that before Eve had been made out of Adam’s rib, Adam’s body had contained both sexes, and that asexual reproduction was possible in this original, androgynous state. Given an extended period of celibacy, he believed, the human body would restore itself to the Adamic condition, allowing it once again to reproduce on its own.

Despite the attention Rapp’s theories paid to procreation, the Rappites’ sense of history was radically curtailed—Rapp’s chiliastic dream posited that within his lifetime the end of days would arrive. And while there would seem to be a contradiction between utopianism and end-times thinking—the former trying to bring about paradise in this world, the latter often willing to go through intense suffering in this world in the belief that it will usher in the apocalypse—Rapp’s project offered a resolution, if an unstable one, of the divide. The end times and attendant salvation were coming, but only for those individuals cleansed by engaging in the right rigid lifestyle that would, almost as a byproduct, enact utopia on earth.

Much has been made of the nascent communism of the Rappite community: members were forced to sign a contract relinquishing their property to Rapp and his associates for their express use, ostensibly for the benefit of the community. But it’s the industry, in both senses of the word, that marks out the Rappite project and offers up the most interesting analysis.

Rapp’s Harmonie settlement was in many ways an industrial powerhouse. The settlers used the Wabash River as a source of energy, but they were also among the first to bring steam power to the region harnessing it for their cotton mill and their threshing machine. Notably, the Harmonists occasionally employed dog-powered treadmills to run some of their lighter machinery—a large dog could often be seen walking on a treadwheel located 12 feet off the ground in the brewery, its revolutions pumping in water for the brewing process.

Just as a doctrine of hard work powered the Rappites’ efforts, a similar doctrine of efficiency ruled their building projects. Among the houses and dwelling places in the town, there was a degree of diversity, though in general the Rappites’ homes demonstrated an impressive amount of prefabrication and standardization, given the age. By 1824, when Rapp sold the property along with all its additions and buildings, moving the majority of his followers to a third and final settlement in Pennsylvania, the colony boasted 2,000 acres of cultivated land, including apple and peach orchards, vineyards, a three-story water-powered merchant mill, a cotton factory, a tanyard, two distilleries, the aforementioned brewery, and two granaries.

The automation and modularity the Rappites’ nascent industrialism gestured at can seem anathema to their stated project, which was centered on labor and hard work. Their factories, of course, took a great effort to construct—it’s only in the light of the Rappites’ perpetually delayed, almost asymptotic apocalypse that their industry makes sense. Building an industrialized town was a heightened effort, the products of which—increased ease and leisure time—they were never meant to enjoy, and in fact enjoyed only briefly and accidentally before being uprooted by their leadership.

While Owen’s later attempt at utopian living contained an element of self-governance—he was convinced that a certain political common sense would eventually flatten and homogenize his communities, that given the proper material and spatial conditions, a democratic process would naturally emerge—Rapp’s project was essentially autocratic in nature, which allowed for inconsistencies and confusions of purpose to be glossed over. The incoherence of his theology resulted, often, from passionate misreadings of canonical texts. What, for instance, was the point of establishing a semi-industrial, highly organized community if it would be entirely unpeopled in a generation? And what would be the point of developing the ability to reproduce asexually if the end of the world were only a few years off? For his followers, these contradictions were for the most part easily resolved in the totalizing logos of Rapp’s personage. For Rapp, they might even have been an intentional strategy.

Robert Dale Owen, whose father would buy the Harmonie properties in 1824, speculated that Rapp “desired to sell Harmony because life there was getting to be easy and quiet…and because he found it difficult to keep his people in order excepting during the bustle and hard work which attended a new settlement.” There were other concerns, of course—the town’s distance from major markets was a problem that would be eliminated by the Rappites’ eventual move back to Pennsylvania—but by the early 1820s even Frederick Rapp, George’s son, had grown concerned about the idleness and restlessness that led some community members to question why they weren’t allowed to enjoy the fine products of their labor and were forced to sell them off instead.

In other words, abandonment was built into the project—outside of heavenly salvation, there was no end to the labor of being a Rappite. Rapp’s utopian project was divorced from social engineering of the sort that often blights technocratic attempts to steer humanity towards a more harmonious existence on earth—the Rappite way of life wasn’t designed to produce an ideal citizen, worker, or human being; rather, the ideal being was produced immediately, in the moment of obeisance.

Rapp’s utopia, then, was in practice a form of control, a redirection of labor—utopia as a continuous process, a liminal state; while salvation would one day arrive from above, the earthly project was never finished. Utopia was not the absence of labor—as it was, to an extent, for Owen, who estimated that in his ideal community a 15-hour workweek would be commonplace—but its perfection into a sealed system, the products of which were ultimately inconsequential. As historian Karl J.R. Arndt put it, “In George Rapp’s Society, with all its apocalyptic curiosity, there never was room for a dream of a workless millennium.”

A Brief Owenite Interlude

Like Rapp, Robert Owen, a wealthy British industrialist who’d made his money with textile mills, had evolved his own abstruse theories of social development. From 1800 on, he’d worked to develop a planned mill-town community in New Lanark, Scotland, though problems had quickly arisen—petty crime and drunkenness persisted among the workers, whose living conditions were still comparatively poor and crowded.

In search of a blank slate to perfect his social theories, Owen turned to the New World, purchasing New Harmony from the departing Rappites in 1824, where he planned to mount a similar experiment in line with the economic and social theories of Charles Fourier.

New Harmony, as envisioned by Owen, was intended to serve as a model of communal living, one the United States legislature could take up and apply elsewhere as the country continued to expand. Owen’s dream, like a stalled vision of Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis, was of a country made up of thousands upon thousands of his communities. His lobbying wasn’t without results—on two separate occasions in 1825, he delivered addresses before the House of Representatives attended by Thomas Jefferson, among others—though his ideas seem to have been merely listened to rather than seriously entertained.

Owing to the problems at his New Lanark community, Owen’s project was aimed explicitly at social engineering and started out with eugenicist overtones. His original proposition called for a group of individuals of “superior dispositions” and allowed that while “persons of color” might be permitted “as helpers, if necessary,” they’d be better off setting up their own communities in Africa, or, failing that, “in some other part of this country.” But the ambition of his plans, combined with impatience, proved an early obstacle to their successful enactment.

Before the intricacies of community life had even been fully hashed out, Owen composed a manifesto inviting any and all who held similar views to travel to New Harmony and begin the work of building his vision. After purchasing the town, Owen traveled for a year; when he returned in 1825, he found a jumbled crowd of passionate idealists and, in the estimation of William E. Wilson, author of The Angel and the Serpent, “an equal number of crackpots, free-loaders, and adventurers whose presence in the town made success unlikely.”

From this precipitous beginning, the town established a preliminary constitution, one less strict than the founding contract of the Rappites. Members worked to earn credit that could be used at the community store—alternatively, those with pre-existing capital could convert it into credit to be used at the same store. The structure of governance was a loose affair. A board was composed of four members chosen by Owen and three elected by the community.

Owen’s ideal community, while never built, helps to elucidate his views, which were otherwise variable and often unclear. The town, in his vision, was spatially regimented and highly planned, relying on a phalanstery model—or hollow square—developed by Fourier as the community’s central structure. The square itself was designed to have equal sides of 1,000 feet. Inside the square would be the town’s institutions, including a chapel, committee rooms, laboratories, a ballroom and concert hall, and so on. Bordering the square would be three-storey residential buildings that reserved the first two floors for families and young children and the third for older children and unmarried adults.

In the actual town, management was, for the most part, an ad hoc affair. Labor—which occurred in the industrial buildings left behind by the Rappites, as well as a few additions—was divided departmentally, with six sections that included agriculture, manufacturing, commerce, and education; superintendents were in charge of direction work within each department. Regular schisms and arguments within the community, however, meant that reorganizations were frequent—Owen, absent for the most part, seems never to have given the nitty-gritty details of working out his vision the attention they needed.

Ideologically, Owen’s socialist proclivities stemmed more from his great belief in perfecting processes than anything else. As Christman writes, Owen “was the type drawn to socialism because he thought it efficient, not because he thought it moral.” In many ways, in fact, Owen’s prevision was hardly one of utopian socialism—community wasn’t the a priori principle of the folk society, as it was with Fourier—and might instead best be viewed as a forerunner to Henry Ford’s Village Industries of the interwar years.

The political function of utopias, as described by Christman, seems more evident in Owen’s experiment than in Rapp’s. “A utopia acts as a rudder on the future: it provokes friction, inconvenience, wonderment, bending the world ever so slightly more its way.” Under Christman’s rubric, failure is beside the point—like a collapsed star, the failed utopia exerts a gravitational influence on historical progress.

As a venture, the town itself was never profitable, which is one of the main reasons Owen ultimately abandoned the project. His hands-off approach to managing it meant, as well, that there were significant interpersonal frictions within the commune, and few members committed to a full ideological buy-in. Internal dissenters disagreed with Owen’s faulty management, and several insalubrious characters even took advantage of the commune’s policies to seize land. In 1827, the socialist contract of New Harmony was dissolved. Owen returned to England, living in London and continuing to pursue his native business ventures.

What Owen’s endeavor ultimately can be said to have traced is the tendency to use the Midwest as an experimental capitalist playground: the historian Arthur Bestor coined the phrase “backwoods utopias” to describe isolated experiments, like Owen’s, that sought to develop a modular blueprint for communal living. The prophetic power of Owen’s utopian socialism, its attempt to bend the future towards it, would have benefited as well, one presumes, from the town’s location on the then-fringes of the United States—a pioneer, after all, being a prophet in his own small way.

Afterwards

What exactly is left of New Harmony is an interesting question, one that often haunts writers drawn to the subject. The historical record for the century that followed Owen’s abandonment of his Indiana project isn’t empty by any means. After 1828, the town fell under the stewardship of William Maclure and played host to laudable educational reforms and scientific endeavors. From 1830 on, New Harmony entered a period of comparative quietude. Owen’s project had served as a seedbed for other, smaller experiments, while the town itself was supported in part by the minor aristocracy formed by Owen’s descendents. Two of Robert’s sons, David Dale and Richard, became geologists and assisted for a time with the town’s revolutionary schooling program. In 1832, Robert Dale Owen, after a sojourn abroad, returned to New Harmony and was eventually elected to the Indiana legislature.

Though it would be inaccurate to describe the state of the town as a sort of class-based feudalism—the Owens’ direction subventions were few—their national prominence brought attention to the town, while their continuing presence presaged the brand of nearly touristic philanthropy that would come to the town’s rescue in the 20th century. Given New Harmony’s size, a gentry was always going to be unlanded, a peculiar graft—in other words, a subsidizing presence, like Robert Owen’s, drawing capital from other locations and sources and funneling it into the passion projects of the town.

By the turn of the 20th century, the radical experiments that had shaped the town had essentially disappeared, and the town was left to stagnate or drowse, as depicted in Marguerite Young’s non-fiction account Angel in the Forest, written in the 1940s. “New Harmony, once so supernatural,” she writes, “has subsided into easy naturalism, like that suggested by James Whitcomb Riley’s poetry.” For Young, “a feeling of both tedium and voluptuousness” shrouds the town, as well as a sense of “desolation…since nothing lingers so like the memory of failure, especially if it has sought the extreme perfection.”

A sense of hauntedness hung about the town, a feeling of being surrounded on all sides by lost futures, potential dreams that, given one or two altered circumstances, might have come to fruition. A utopia is always temporally split, existing at once as the kernel and as the envisioned fruit; a failed utopia is more haunting than most historical failures since its success might have entailed a higher reorganization of the world. The failed utopia is a wound that calls out for a salve, the failed prophecy a lie that necessitates redress.

Which is why so many strange things seem to happen in New Harmony, why the town seems to be locked in a cycle of eternal return. Restarting the town necessitated a startling influx of capital, which is exactly what it eventually received under the patronage of Jane Blaffer Owen, the wife of Kenneth Dale Owen (a direct descendent of Robert) and an oil heiress in her own right. Starting in the 1940s, Jane Owen launched a town-wide restoration project that would take up the greater part of the second half of the 20th century.

Under Jane Owen’s supervision, cabins were restored as well as brick and frame houses, and in 1962 she commissioned Philip Johnson to build the Roofless Church, an open-air site of worship one end of which was a wooden dome 50 feet high and covered with pine shingles. The next year, the existential theologian Paul Tillich was brought to the town to deliver a lecture titled “Estranged and Reunited: The New Being.” A small park was dedicated in his honor.

Jane Owen’s revitalization of the town was an attempt to create a spiritual renaissance that, once again, would be adaptable and scalable to the world as whole. Preachers, artists, poets, and musicians were regularly brought into the town to perform and stay.

By the time I was born in 1994, there was still a certain energy about the town. The Rappite granary was fully restored in 1999 and converted into an events space and music hall, and Mrs. Owen was still driving about the town in her old Model T, presiding over visitors and conferences and events. When she died in 2012, however, the projects slowed, and nowadays the town is once more sliding into the backwater—the vineyard she financed has been uprooted, the peony fields she backed have long been overgrown, and the town has lost much of the touristic appeal that drove its economy.

The buildings on Main Street shuffle rapidly between new stores—antique doll shops and aromatic soap stores and fluorescent pizza parlors; the ramshackle general store I grew up with, Amy’s, is now an upscale home goods store. Throughout her life, Mrs. Owen had stringently opposed chain businesses in New Harmony, but in 2019 a Dollar General was built at the entrance to the town. “From back about 50 years or so ago we had a lot more gas stations and grocery stores that kind of thing and it went backwards if you will for a while,” the town council’s president explained, paratactically, at the time. “Now with the dollar store, the convenient store, it’s beginning to come back the other way and we’re starting to get some more stuff into town.”

At the time of Mrs. Owen’s passing, there was a sense in the town that a long reprieve had come to an end, that the monoculturization she’d stringently kept at bay for more than six decades was closing in like a storm. When I go back for visits, my feelings are always conflicted—in many ways, Mrs. Owen’s cultural revival was an imposition on the small Hoosier town, many of whose working-class residents couldn’t have cared less about her events and projects, save for the jobs and security they provided in an increasingly post-industrial landscape.

But at least, for a while, it worked. There sometimes seems an irony in the twice-failed town of New Harmony, hollowed out by the absence and outsourcing of the industrialization employed by the Rappites, and abandoned by the brand of gentrifying philanthropy embodied by the Owens. Left to its own devices, absent zealotry, absent idealism, the town reveals itself as hardly unique at all—not the product of vision or prophecy, but the victim of increasingly neoliberal and often abstract market forces.

Reading Utopias Now

Today, Tillich Park is a sad copse of pines stripped of their branches almost halfway up their trunks. And while Tillich’s forecasting of the birth of a New Being went the way of Rapp’s own prognostications, it reveals something important about the nature of prophecies in general. Embedded in the concept of prophecy is an overextending gesture, a profligacy, whether that means promising more than could possibly be borne out by time or simply making too many predictions, some of which cancel each other out.

Prophecies are remade and repeated, casting their failures ahead of them in a way that seems to impose a challenge on whoever comes upon them—failed prophecy is an invitation to try again. Rapp often seemed to be adjusting his prophecies on the fly, uprooting his followers again and again without fundamentally altering the future that he promised. Owen’s prophecies were of another, more workaday sort—like today’s venture capitalists, he shuttled skittishly from investment to investment, constantly trying something new and banking on a future market dominance.

Seeing utopian communities clearly requires a similar temporal gesture. Viewing them outside of their time would seem to be a recipe for disaster, at least as far as American scholars are concerned. The radical economic nature of both the Rappite and Owenite projects, as well as the fanaticism with which they were undertaken—whether it was the fanaticism of a group, as with the Rappites, or the fanaticism of an individual, as with Robert Owen—often prove distracting to the critical eye. Preconceptions cloak history and take flight in the absence of facts (most of the authoritative texts on the movements were written more than 50 years ago, when access to documentary evidence and sources were scant).

Obsession is one possible result. Angel in the Forest, whose author was herself a bohemian and visionary political dreamer best known for her opium-infused 1,198-page novel Miss Macintosh, My Darling, assumes a vatic tone throughout. Its diction is high, occasionally apocalyptic, and its descriptions are sweeping. Scholarly only in the loosest sense—Young’s technique is valedictory and impressionistic, obsessed with the passionate magic of the past—the book, at least when I was young, was almost contraband in the community, unstocked in the visitor’s center, though you might have found a copy at Golden Raintree Books. Mrs. Owen, my father told me, considered it a trashy and irresponsible expose.

Running counter to Young’s feverish reimagining is the work of Wilson. Published in 1964, The Angel and the Serpent is easily the most readable of the available histories of New Harmony, but it falls prey to the anti-communist tendencies of its era. The Rappites come in for a drubbing—litigious, money-grubbing, and aggressively parochial, they strike Wilson’s eye as unrepentant foreigners. “They not only refused to be assimilated,” he writes, “they refused to share with any degree of altruism the responsibilities of citizenship in their adopted land.” Wilson, steeped in scholastic purity, seems to have just barely pulled himself back from describing the Rappites as un-American.

How do we imagine utopias in the 21st century? There’s a tendency in the popular imagination to view attempts at utopian living as tenuous dreams upheld only temporarily by a supernatural force. The complex interplay between fanaticism and capital is often lost, outshone by the movements’ outward fervor, so that it becomes difficult to discern that a massive influx of capital can hardly do more than produce the mirage of a just, egalitarian society.

Like so many Midwestern small towns, New Harmony has become its own sort of mirage. When I visit, I find that my childhood friends are living in historic buildings, or above the old movie theatre; they work in the nearby city, commuting back and forth, or else at the local senior home, its population miraculously steady through everything else. It’s as though, I often think, the town were an outpost, a placeholder—waiting to be replaced, or to disappear.

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.