James Baxter

Blow-Out

ISSUE 98 | TEETH | JUL 2021

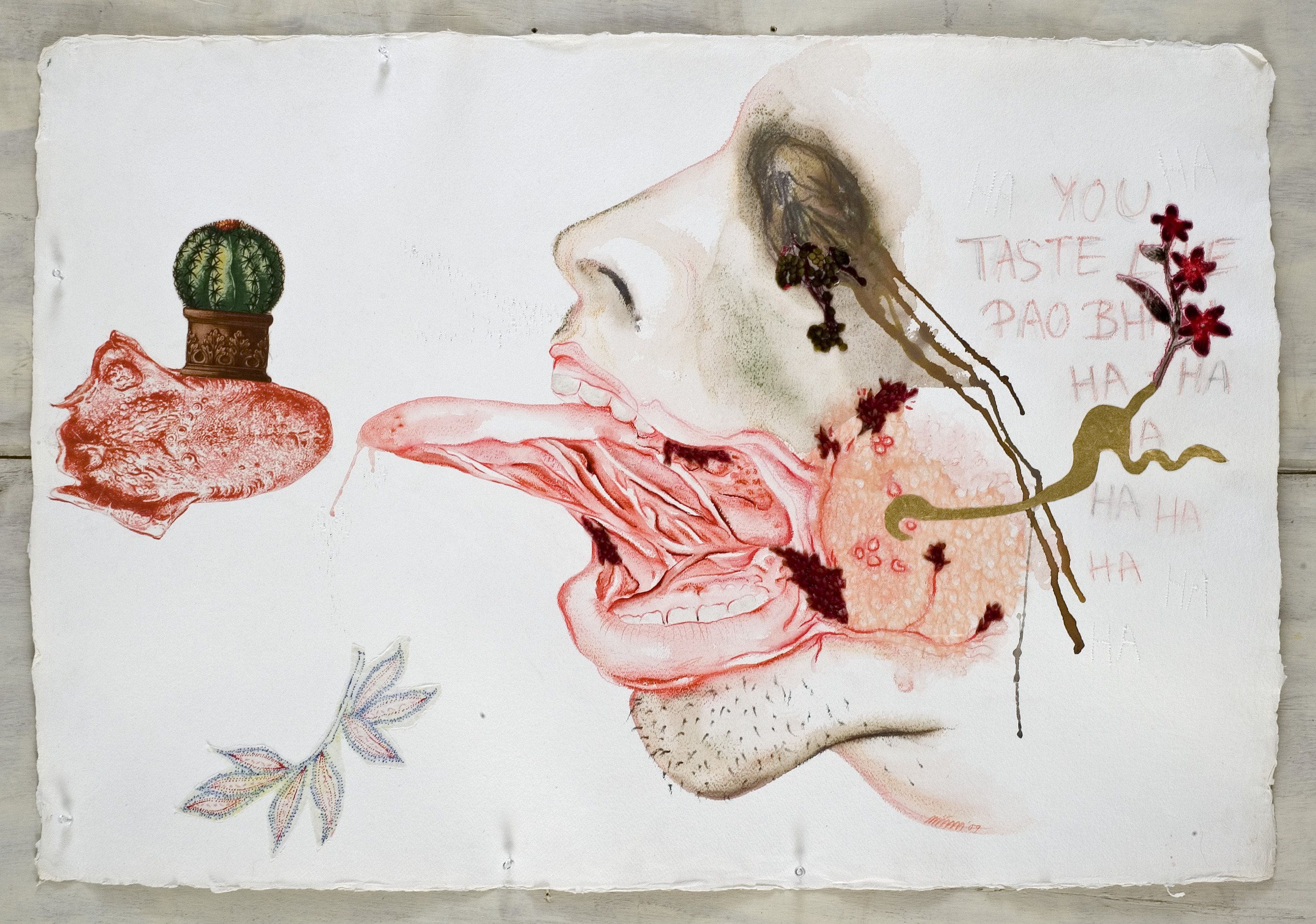

You taste like paobhaji, by Mithu Sen, 2010

Jean-François Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy (1974) is a book about desire at breaking point. Not just any desire but the kind of irrational drive that seizes the body in dizzying bursts of ecstasy, obsession, and suffering. In his opening image, Lyotard imagines a vast, ephemeral skin stretched out to form a Möbius strip, a pulsating medium for the flow of overwhelming “intensities.” “Intensities” are key for Lyotard, referenced throughout the text but seldom defined outside of the promise of some illicit, unspeakable thrill.

How are these desires to be marshaled into something larger than ourselves, and beyond what point do they explode into great, ejaculatory fireworks? Like the elastic skin of the opening passage, these desires are to be found everywhere and touch everything from one’s eccentric sexual fantasies to the frenzied production of capitalist economies. In his most outrageous claim, Lyotard declares that the British proletariat enjoyed its immiseration in the factories and mines of industrial capitalism, reimagining physical exhaustion as a giant feast, the force-feeding of intense, masochistic delight:

Why, political intellectuals, do you incline towards the proletariat? In commiseration for what? I realize that a proletarian would hate you, you have no hatred because you are bourgeois, privileged, smooth skinned types, but also because you dare not say the only important thing there is to say, that one can enjoy swallowing the shit of capital, its materials, its metal bars, its polystyrene, its books, its sausage pates, swallowing tonnes of it till you burst…

Clashing with Marx’s notion of “false consciousness,” all revolutionary friction is smoothed over in great waves of passion. There is no subversive region beyond the domination of capital, Lyotard feverishly asserts, only the wandering investments and disinvestments of desire.

Lyotard’s clumsy provocation alienated many from the left who found much to dislike in the book’s indirect celebration of unconstrained capitalism as an engine for the release of libidinal energy. The author himself would later disown Libidinal Economy as his “evil book,” “the book of evilness that everyone writing and thinking is tempted to do.” If the idea of the book’s “evilness” might seem a bit quaint, that of an itching “temptation” towards corruption remains menacing.

It is worth keeping in mind the more recent favor that Libidinal Economy has acquired among notable figures from the political right such as Nick Land, whose advocacy for the acceleration of capitalism’s destabilizing tendencies is presaged in Lyotard’s more explicitly nihilistic sequences. But at its disagreeable core, the book’s central investigation into the kind of enforced enjoyments of capital raises difficult questions about the emancipatory potential of desire. Lyotard has little faith in the libido to properly manifest as a counterforce capable of meaningfully changing the relation between one’s own body and that of others. Critique is impossible; all that is left for one to do is to enjoy, mercilessly. So eat up.

* * *

A vast and thanatopic feast is also envisioned by Marco Ferreri’s 1973 film La Grande Bouffe (released in English under the title Blow-Out), which tells the story of four well-to-do acquaintances who retreat to an extravagant townhouse with the purpose of eating themselves to death. Like comparable works by Luis Buñuel, Věra Chytilová, Peter Greenaway, and others, Ferreri’s film explores the connection between eating, sexuality and death, maintaining a cult following for the frequency of gross-out moments as the four leads eat, vomit, fart, and fuck their way through the film. At the same time, La Grande Bouffe rewards a closer look into the kind of monomaniacal “intensities” privileged by Lyotard, instead drawing attention to the kind of pleasures that are necessarily stifled by the relentless motor of capital exchange.

We are introduced to the film’s main characters one by one as they prepare to leave their families and careers for the debauchery to follow. Chef Ugo (Ugo Tognazzi) packs his finest kitchen knives, regaling his bored wife with the tale of their sentimental importance (a story we are led to believe he has told many times over); meanwhile, Michel (Michel Piccoli) ties up a number of loose ends at a glitzy studio, where he looks forward to “rest and solitude” from his job as a TV producer; in an absurd sequence, one of the attendants to airline pilot Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni) rolls a giant wheel of Parmesan down the aisle of a cabin. When we meet the childish and Oedipally fixated judge Philippe (Philippe Noiret), he is being implored not to depart by his childhood nanny, with whom he also appears to maintain a sexual relationship (she desperately reminds him not to forget “who suckled you when you were young”). Given the excessive indulgence of the “gastronomic seminar” at the film’s center, it is easy to overlook the quietly miserable and awkward erotic displacements of these early sequences, which establish a twitchy, neurotic tenor through close-ups of tapping fingers and gloved hands.

As a quartet, the actors (performing under their own names) present a cross-section of French-Italian machismo best embodied by the frequent Fellini collaborator Mastroianni, whose unmoved and weatherworn visage serves as a kind of visual shorthand for the louche decadence evoked throughout. The womanizing Marcello is also instrumental to the film's sleazier excesses, encouraging the friends to invite a group of sex workers to participate in the feast and cater to their sexual appetites. Appalled at this prospect, Philippe reminds the acquaintances that they “are not participating in some vulgar orgy.” The boorish misogyny of the group is accompanied by a suffocating gentility, with many of the characters struck by crippling episodes of guilt—whether that be Philippe’s stiff sense of propriety or Michel’s disgust at his own explosive flatulence (he will expire later in the film from a ruptured colon).

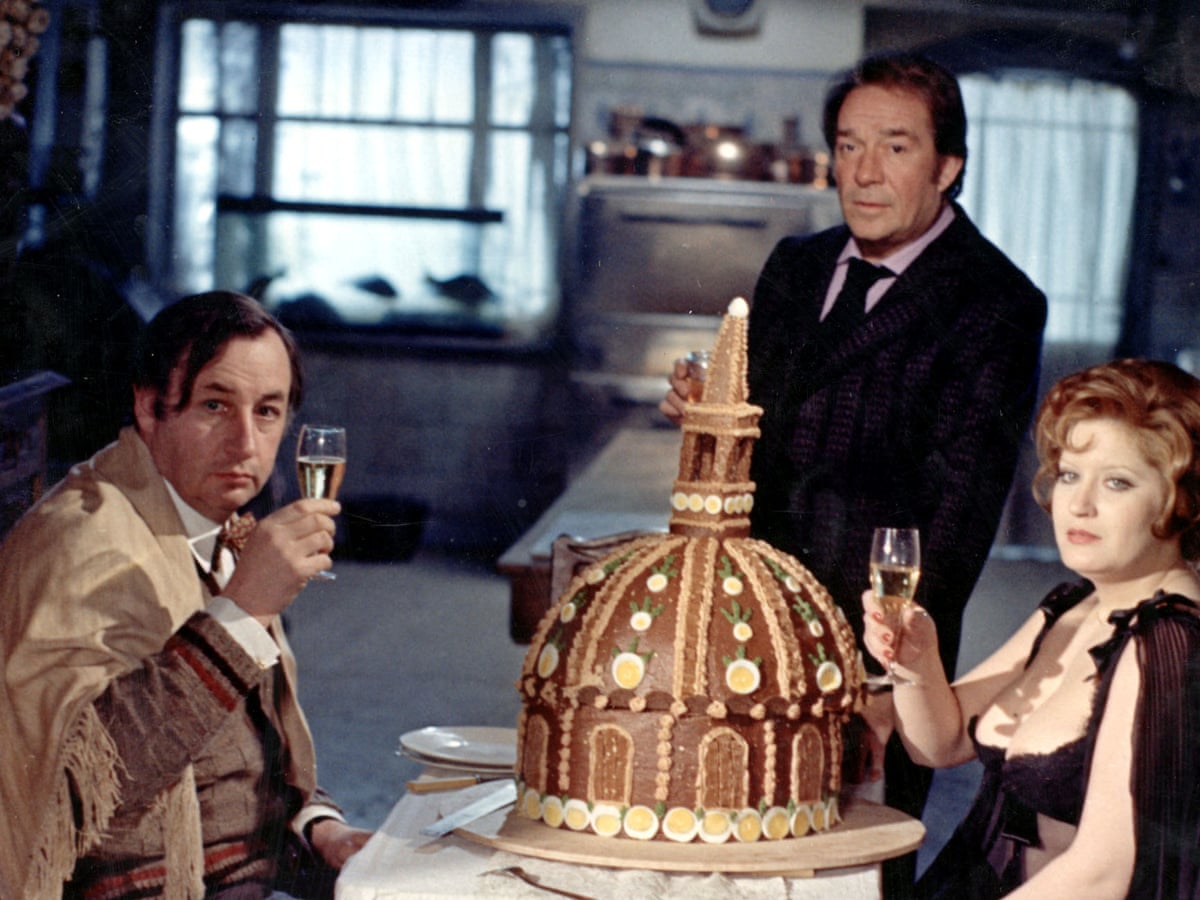

There is certainly a degree of nihilistic fun to be had in watching dressed-down A-listers perform grotesque acts for entertainment. And yet the friends are eager to remind us of the cultivation of their exploits—winkingly invoking the kind of refinement that, on the face of it, money can’t buy. Philippe casually references the “unrecognized” and “slightly surrealist” French writer Raymond Roussel for his interest in the radical potential of mixing three courses in one. Ugo’s “awesome” masterpiece—a monstrous triple liver pâté shaped like the dome of Saint Peter’s—is nothing less than “a poem.” Their death drive has quite the pedigree. No “vulgar orgy”—alas, this is art.

* * *

Much of the immediate critical response to La Grande Bouffe would highlight the film’s seemingly unlimited resources of perversity (Catherine Deneuve, Mastroianni’s lover at the time, was reportedly so appalled that she wouldn’t speak to him following the film’s debut at Cannes). In keeping with its rather meager theatrical opening in America, The New York Times would offer a lukewarm assessment of the film’s “doomy and pretentious” vulgarity while overlooking the film’s explicit echoes of 20th-century transgressive art.

Lyotard’s nihilistic excursion into the politics of desire similarly reads like a work of (singularly bamboozling) erotica. Avant-garde figures such as the Marquis de Sade, Pierre Klossowski, and George Bataille inform the text’s lurid corporeal images of eating, defecation, and violent sexuality. Lyotard’s chief fascination with “intensities” owes much to the pagan spectacle of Bataille, whose hallucinogenic essay “The Solar Anus” provides one view into extreme passion as an “eruptive force” emanating from “below.” Anticipating Lyotard’s great libidinal skin, Bataille affirms the disruptive filthiness of the body as the reason why communist workers appear in the eyes of the capitalist to be “as ugly and dirty as hairy sexual organs.”

Building on this lineage, Lyotard asserts that one must similarly approach Marx’s corpus as an erotically fixated work of art. Marx too, Lyotard suggests, enjoyed and was seduced by capitalism’s bottomless supply of pleasures. In a bizarre piece of philosophical parody, Lyotard imagines Marx as “a strange bisexual assemblage”: both “old man” (a prosecutor and a rationalist armed with a carefully tallied file on the suffering caused by the accused capitalist) and “young woman” (a kind of moral conscience who is both attuned to and terrorized by the libidinal “intensities” engendered by capitalism itself).

In his most sustained exploration of the feminine Marx, Lyotard renders her as a fundamentally nostalgic figure yearning after an unsullied wholeness beyond the “universal prostitution” of commerce. Fleeting moments of “exorbitant” intensity give rise to spasms of pleasure reminiscent of the involuntary yelps that seize the friends of La Grande Bouffe. Despite the fact that Lyotard claims to “abandon masculinity” and “listen to femininity,” he exhibits a demoniacal glee in vulgarizing the rosy sentimentality associated with “Little Girl Marx.” Later in this discussion, he invokes the more explicitly despotic vision of the Marquis de Sade, comparing the exhaustive “intensities” of Sade’s manifold atrocities to those engendered under capitalism. As in Sade, the implication remains that those who dominate capital may be best placed to enjoy the unspeakable pleasures of the libido.

Sade’s first (and unfinished) novel The 120 Days of Sodom (1785) also casts a profound shadow over the enclosed world of La Grande Bouffe. In both Sade’s writings and Ferreri’s film, a group of quasi-aristocratic friends withdraw from society in order to take part in acts of debauchery that end in death. Though Sade, now a commodified and kinky icon, has become a firm part of the libidinal economy (retaining just enough of the aura of taboo for his modern descendants to sell designer bottles of wine, scented candles, lingerie, and luxury meat), his works speak for themselves as highly influential studies of desire, violence, and exhaustion.

Composed in miniscule script on a single roll of paper during the Marquis’s imprisonment in the Bastille (immediately to prior the prison’s storming), 120 Days follows four wicked libertines as they retreat to the remote Silling castle with their wives, virile male lovers, young boys, girls, and procurers—the latter doubling as depraved orators whose tales of infamy function to inspire the frenzied imaginations of the group. Promising readers “the most impure tale ever written since the world began,” the horrors inflicted upon the (mostly pre-adolescent) bodies of the victims are described by the narrator with a jarringly companionable voice replete with nods to the “friendly reader.”

The influence of 120 Days reigns over La Grande Bouffe’s scattershot mix of references to the avant-garde and popular culture (at one point Ugo pulls off an unsettlingly convincing dress-up as Marlon Brando). Philippe is affectionately labeled “the President,” echoing Sade’s filthy hero President Curval (“few had been as free in their behavior…but, entirely jaded, absolutely besotted”). Undoubtedly more chilling is the company’s desire for a “whore menu,” with the only food left uneaten splattered on the bodies of the women corralled into the feast.

Where Ferreri’s comical restyling of Sadean aesthetics concludes with the self-destruction of its central quartet, Sade’s novel serves as a catalogue of unbearable sexual cruelties to be inflicted on others. Devoid of mystery, the literally and metaphorically insular universe of 120 Days functions as a kind of enclosed pseudo-state in which the assorted victims are circulated between friends, bearing little significance beyond their immediate fungibility. Unlike Lyotard and his poststructuralist contemporaries, Sade the author remains something of a rationalist in this regard: the novel’s first 70 pages are taken up by the systematic enumeration of the rules and statutes of their libertinage, including a minute textual illustration of each member of the party down to the appearance of their teeth.

And yet if pleasure is something that is ruthlessly inflicted in Sade’s writings, it also suggests a seismic break from conservative sexual morality—knee-jerk revulsion often masking the thornier radicalism of Sade’s legitimization of “unlawful” sex. The immense esteem in which the company of 120 Days hold anal pleasure (wildly controversial in the author’s time) uncouples the libido from reproduction and towards pleasure for its own sake. As always, this is filtered through Sade’s dark material imagination, accompanied by a kind of pervading emotional hardness and attention to the hay-wire body as a glitching automaton. Simone de Beauvoir’s much-celebrated 1951 apologia “Must We Burn Sade?” characterizes the Sadean libertine’s disposition of psychological “apartness”:

The male aggression of the Sadean hero is never softened by the usual transformation of the body into flesh…. We see how desire and pleasure explode into furious crisis in this cold, tense body, impregnable to all enchantment. They do not constitute a living experience within the framework of the subject’s psycho-physiological unity. Instead, they blast him, like some kind of bodily accident.

It is no mistake that orgasm in Sade’s novel frequently elicits bouts of extreme anger, violence, and blasphemy on the part of its protagonists.

Ultimately, the ethical imperative towards unlimited freedom and the centrifugal expansion of the passions in Sade favor those who can reconcile their private desires with the world through tyranny (a nostalgic fantasy of aristocratic domination for the long-imprisoned Marquis). These tensions are rendered explicit in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s infamous adaptation, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), in which the 18th-century horrors of Silling castle are transported to fascist Italy. (In a further striking crossover, fellow Italian provocateur Ferreri would maintain a life-long friendship with Pasolini, even starring in the 1969 satire Porcile, which investigates the roots and origins of European fascism through similarly lurid means.)

Often held up as one of the most controversial works of 20th-century cinema, Salò pushes the question of whether one can represent excess and cruelty without surrendering to it. For the director, the antidote to unfettered sexual violence is a kind of libidinal disinvestment, resulting in periods of rumbling inertia, often redirecting focus onto the implicit cruelty of the voyeuristic gaze. In the calculatedly drab opening moments, the four besuited friends draw up their arrangements for the ensuing debauch, with the Duc declaring: “All things are good when taken to excess.” By the unbearable finale, the audience is forced into the position of the complicit onlooker, watching through a series of POV shots as the libertines view the rape and mutilation of their victims from afar.

In few other modes of human behavior is the link between the satisfaction of desire and the destruction of the desired object quite as close as that of eating, and both La Grande Bouffe and Salò give respective accounts of the vicious impulses of desire through food. In the latter film’s most spectacularly confrontational moments, victims and torturers alike feast on human excrement, embodying the Sadean epigram that “the greatest pleasure is derived from the most infamous source.” A marker of the friends’ seemingly unlimited control over their subjects, all excretions are carefully monitored, with the harem of girls and boys fed at peculiar hours to encourage larger emissions. Further collapsing destruction and desire, the turd in Salò (a somewhat simplified translation of the more complex fetishism of Sade’s novel) serves as the most wretched and longed-for object, an enforced transvaluation of wasted substance through force, bearing all the aggression of the Bishop’s sneering injunction: “eat shit.”

While remaining gentler in its transgressions, La Grande Bouffe nevertheless revels in the sustained elision of the difference between food and shit. Despite the opulent milieu and the abundant fare available to our hedonists, the food served throughout the film appears conspicuously unappetizing. A suckling pig is covered in a peculiar green paste; the roasted cockerel is decorated with ornamental skulls in what Philippe deadpans is a “quite melancholy” display. The most explicit reduction of luxuriance to crap is rendered in an outrageous moment in which the toilet erupts in a gigantic vortex of excrement. Soon enough, the characters themselves undergo a similar passage into waste. As each member of the group dies, their bodies are packed into the freezer, the corpses occasionally glimpsed from the kitchen window.

* * *

Who desires in Lyotard’s incantation of “a discourse at maximum intensity,” and from whose mouths are these boundaryless cries pulled? If the wretched course of the “pimp capitalists” inspires the moral indignation of “Little Girl Marx,” then what forms of affect, of enjoyment end up being alienated under the enforced terms of subjugation established by capital? One option is outlined by Italian activist and philosopher Mario Mieli, whose work Towards a Gay Communism: Elements of a Homosexual Critique (1977) gestures towards forms of happiness—in particular, the revolutionary promise of gayness—contrary to the “mutilation” of Eros under the violent and repressive function of heterosexual “normality.” Taking aim at the concomitant repression of mandatory “educastration,” Mieli’s writing is attuned to the limits of sexual identity as such, remaining steadfast on the nature of desire that “reaches towards transsexuality.” In Mieli’s most bracing assertions, he foregrounds the “polymorphous perversity” of a universal transsexuality, adopting Freud’s theory of the multifarious and undifferentiated libido of infant children in modes of pleasure that exist outside of societally prescribed sexuality.

Often arrestingly funny, Mieli is indebted to figures such as Pasolini and Sade (not without a degree of irony, Mieli quotes extensively from Sade’s later novel Justine (1791) as an exemplar of the ecstatic joys of anal sex). While Mieli shares with Lyotard a fascination for the ways in which libido and capital are imbricated, his writing bears with it a practicality that is lost in Libidinal Economy. Homosexual desire, Mieli reminds us, is “an advance, not a concept”: a call for the collective reinvention of “normality” through revolutionary action. At the same time, he also does not lose sight of the de-sublimation of perversity in commodity form (as it is “studied, classified, valued, marketed, accepted, discussed”). In this regard, there are moments in which the re-enchantment of filthiness is perceived as a precursor to new forms of emancipatory openness that do not preclude libidinal attachments to “children and new arrivals of every kind, dead bodies, animals, plants, things, flowers, turds.” Shocking and at times morally irreconcilable (not least for the jarring references to pedophilia), Mieli nonetheless overturns the necessary withdrawal into private intensities glimpsed in Sade, moving us instead towards the public incitement of polymorphic libidinal possibilities.

Halfway through La Grande Bouffe we are introduced to Andrea, a teacher who asks for entry onto the friends’ grounds to teach her students about the 17th-century poet Nicholas Boileau (the estate is home to the lime tree under which Boileau composed many of his odes to sensuality and nature). She immediately catches the eye of the group as a possible addition to their party. While Andrea is initially distinguished by her matronly demeanor (something which attracts Philippe in particular), she remains perhaps the only character properly equipped to enjoy themselves in this otherwise morbid affair (this is also contrasted with the other women, whose enjoyment rapidly diminishes after they glimpse the friends’ disinterest in anything beyond eating). In a scene directly reminiscent of his always indulged but perpetually discomfited relationship with his nanny, Philippe wastes no time in clumsily proposing to Andrea—though the latter’s appetites prove less easy to define.

If Andrea’s character falls somewhat short of Mieli’s utopian horizon concerning the revolutionary abolition of “homo normalis,” her actions throughout the film are marked by an openness to riotous hedonism, as well moments of quieter, and at times even affectionate, sensuality. She engages in sexual acts with each of the four friends; in one funny, grotesque, and oddly endearing scene, she mounts Michel to help release the pent-up gas in his body in bursts of explosive flatulence; elsewhere, she delightedly gives over her bare buttocks to help knead Ugo’s dough. The disparity between the rigidly hetero friends and the more polymorphous desire of Andrea is foregrounded when she is solicited by Marcello, who is immediately struck with impotence; enraged by his inability to perform sexually, he projects his frustrations onto Andrea and the others, childishly lashing out at her “vulgarity.” Andrea seems to recognize Marcello's ineffectual machismo for the parody of male desire that it is, and she remains oddly sympathetic to the epicurean spirit of the feast even as it reaches its deathly conclusion.

Near the end of the film, we find Philippe languishing underneath Boileau’s lime tree (ever the naïf, he still holds hope for his marriage to Andrea). She brings his last meal (a gelatinous-looking cake shaped like two large breasts) as he wishes farewell to his friends, surrounded by stray dogs in a remarkably lachrymose display. While it is left to our own perverse imaginations to decide whether he enjoys this last supper, like the most blinkered consumer Philippe’s dissatisfaction is expressed through hostility to the staff. The butcher’s truck arrives onto the grounds, a vehicular mortuary of animal carcasses. Philippe makes his final complaint: “Tell your boss the veal was second rate.” He dies shortly thereafter, while Andrea returns to the house and the ghosts in the kitchen.