Erica X Eisen

What It Means to Be Alive: An Interview with Ravi Amar Zupa

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

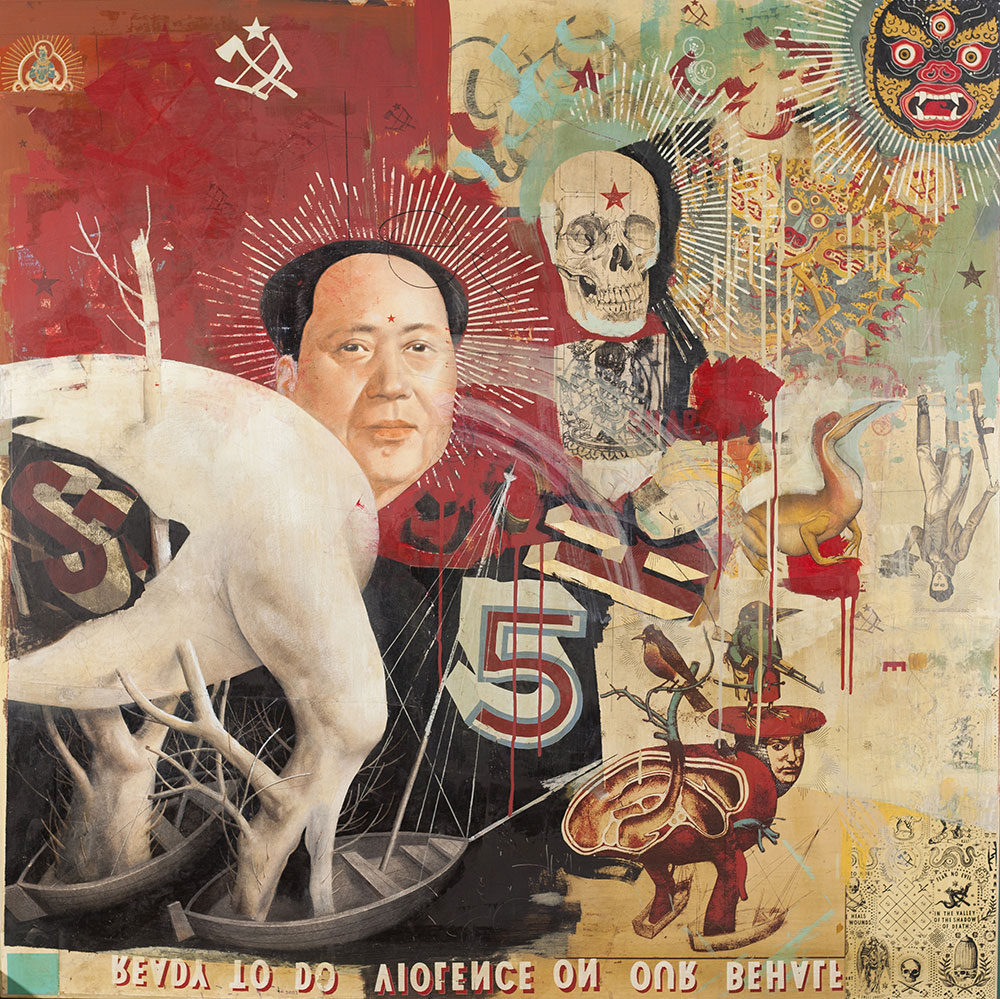

Illustration by Ravi Zupa.

Hypocrite Reader is excited to announce the inauguration of its Featured Artist series. Each issue, we will highlight an artist whose work is thematically resonant with the written pieces. For PROPHECIES, we spoke with Ravi Amar Zupa, a painter, printmaker, and sculptor who currently lives outside Denver, Colorado. His works often incorporate religious imagery. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Hypocrite Reader: I don’t remember now how I came across your work, but I was really immediately struck by it. When we were putting together this issue around this theme of prophecies I thought that your work really vibed with that. I guess the first question I have is how you got on the path of becoming an artist.

Ravi Amar Zupa: My mother is an artist, and taught art to kids for her career. She still does actually a little bit, but she’s mostly retired now. My father was an artist, but he died before I was born, and everybody in my family—there’s five of us—was interested in art when we were young. It was just kind of an ordinary part of life.

HR: Did you get exposed at an early age to the kinds of art historical influences that you play with in your art, or was that something that came later?

RAZ: My mom was raised Methodist and then in New York City in the 1960s she came across Indian religion and got initiated into a religious path that’s sort of a derivative of Sikhism. She lives on an ashram now and is still very much in that community. And my father had been raised a Catholic and converted to Islam for the last 15 years of his life, so there was sort of a thick multicultural influence in my house. And my mom was always looking at art in books. A big part of my home was that kind of art.

HR: And how was your religious upbringing?

RAZ: So the particular path that my mother’s chosen is kind of specific about certain guidelines—children are not just automatically part of it, you’re not really born into it. You have to become initiated, which means going through a process, and you have to be brought in by the guru. So you’re not really an initiate when you’re a child, although people kind of functionally are. But that was what I was raised in, and I did believe in reincarnation and all of that.

HR: How would you describe your religious beliefs now?

RAZ: I identify as a Christian and as an atheist, and I mean both in earnest. I say Christian, because it’s where I’m from, I am a white American. It’s in the air we breathe; you can’t really avoid absorbing the specific ethical sensibilities of Protestant Christianity if you grow up in the United States. It’s in everything, in the television commercials and the billboards and in the interactions with your neighbors. So I identify with that, and I like Christianity in a lot of ways. I don’t believe that there’s any kind of conscious god, I don’t believe that there’s anything that happens after death. But it’s all symbolically true.

HR: To your point about the atmospheric Christianity of the United States—I was raised in a secular household, neither of my parents practice a religion, but I also remember very earnestly believing in Hell as a child to the point that when in elementary school our teacher was talking about the different layers in the inside of the Earth I was very confused because I had assumed that Hell was a geographical location.

RAZ: Where do you think you got it? I mean, that is kind of a specific attribute more than just sort of an ethical framework.

HR: It must have been cartoons, maybe hearing Christian friends or classmates talk about these things very earnestly. I don’t know, it’s a good question. I think part of the “atmospheric” aspect is it’s very difficult to pinpoint because it’s all around you.

So when I first saw your pieces, my first impression was that your painting were collages. Can you talk about how you developed this aesthetic?

RAZ: That’s something that I’m up against all the time—people thinking that I do cut images out of books or blow them up or print them out or things like that, which is a little frustrating because I’ve spent a lot of time learning how to do this. Everything that I do basically starts with just really loving art, and I look through books mainly and find things that are just exciting, just beautiful and remarkable. The way that I feel lit up by art, I get really strong experiences looking at it, I feel so excited and moved by art, and the main consequence of that usually is wanting to cause the same movement in somebody else. That’s really the root of all of it, so I’ll find something that’s exciting and try to decipher what it is that they’re doing that is unique. Every art movement or historical moment has limitations about what they’re able to achieve or what they’re able to see, a lot of times dictated by technology. And those things are so interesting.

HR: And in terms of the texts that you incorporate in your work, how do you choose which texts to draw from, the placement—how do you think about the relationship between text and image?

RAZ: A lot of the times it’s really the most time-consuming part of the process, and I’ll get stuck for long periods trying to think about the right thing to put with something. Maybe Kurt Vonnegut is talking about the same phenomena and part of human life that this Hindu god represents. Not in a very direct way, but more or less they’re talking about the same part of us, of what it means to be alive.

HR: How have you seen galleries and museums adapting to social distancing and closures? How successful do you think things like online gallery shows have been?

RAZ: I think that’s been the trend for a long time now. Most sales, most galleries do the majority of their sales online already, have been for the last 10 years, it’s been ramping up. But there just is such a social element to it. It’s just such an unfortunate idea to think that down the road there won’t be physical locations that are kind of set aside for this kind of stuff in a sort of ordinary way. Obviously museums are gonna continue to exist and very expensive fancy galleries are gonna continue to exist. But it’s cool to have small stuff for ordinary people, ordinary times. I don’t think they have any idea what the fuck to do.

HR: Would you find yourself going through periods where you’re drawn to a specific historical influence or aesthetic style, or is it a more sort of diffuse process?

RAZ: It’s both—but I do have a stable of things that I am the most interested in all the time. Japanese printmaking, Flemish paintings, a lot of Hindu art from multiple moments in history. And there are some things that I really like and am really excited by and moved by but have any interest in doing. A lot of later European stuff—Impressionists and things like that. I like that stuff a lot, but I don’t ever really pursue that.

I do from time to time get negative reactions. It’s rare, and when it does happen, most of the time it’ll be like, “Why is this this way?” I hope that it’s because people can see infused in it a genuine respect and interest and appreciation. There’s a lot of garbage art, art that I think is disrespectful to religions where you’ll have an image of a crucified Donald Duck or something. I do find some of that stuff to be not thoughtful and not making any attempt to think about life—the purpose is to just be challenging. I’m not trying to do that, it’s not something I’m interested in doing. My intention is not to inflame Christians, for example. If I’m using an image it’s because I love an image, not because I’m trying to deface it. The other thing is my own life—I am genuinely a human being who is, my own cultural identity is the result of a lot of mixing of cultures. My name is Ravi, it’s my real name—I didn’t get into yoga and then decide to change my name. And that has ramifications on my upbringing and who I am as a cultural identity.

HR: You were talking about shock art earlier, and my reaction to a lot of that work is that it’s pandering to the viewer by assuming that they would be offended. And in that respect, I’m more offended by the assumption that it makes about me, and how I am supposed to feel, and how it is supposed to be high-handedly deconstructing what I supposedly feel, than I am sincerely in an engagement with the work. I don't know if that makes sense.

RAZ: Which can make it boring.

HR: Exactly—if the entire meaning of your work is that it shocks, what happens when cultural norms shift and that’s no longer shocking?

RAZ: I was reading an article—I think it was in New Mexico, there was a painting of Jesus crucified and a woman went into the museum where this was being shown and hit the piece with a hammer and broke the glass and damaged the piece. And she was just an American lady who is a Protestant who believes in God, and I remember the response being, “Oh, these people are kind of ignorant and they don’t understand it.” And I remember thinking, “If I was in the museum and I saw that art, I probably wouldn’t have taken much note of it, and if I looked around I proably would see a bunch of people not giving a fuck one way or another.” But here’s this person who is profoundly moved by your art, so much so that she’s willing to put herself in legal jeopardy.

HR: It’s an authentic reaction. If you didn’t believe that something was worth destroying, then you wouldn’t have that kind of reaction.

When you get an idea for a piece, is it immediately clear to you what medium a piece should be, or is it something that comes to you as you draft?

RAZ: You know, there’s an odd interchange. As far as two-dimensional work that I do, it is painting and drawing and screenprinting. There’s a back and forth between painting and printing, where I take something that was a painting and I want to make it into a print, and I’ll figure out how to alter it as an image so that it’s gonna be good for printmaking. I have motifs and ideas that I’m really excited about and will revisit over and over again. I have probably 20 pieces that feature St. George and the dragon, and they are in many, many different forms, they’ll be a block print and a drawing and a screen print and a painting. Mostly because that’s so fun to see when you look through books and you see the same character come up in different places: the way that they’re the same and the way that they’re so different. You see St. George painted in the 1800s in England, and then you see the same character in some Russian Orthodox painting from the year 900, and you can tell that they’re the same character because of all these specific attributes, but there’s specific characteristics about what Russian Orthodox paintings do inside of you that is different from what later realistic European painting does. And that’s kind of the fun of it, the satisfying thing for me is finding all the different ways to describe similar things and ways of describing different things similarly.