Hannah Sparwasser Soroka

Cannibals in the World to Come: Thomas Thorowgood, the New World, and the Lost Tribes of Israel

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

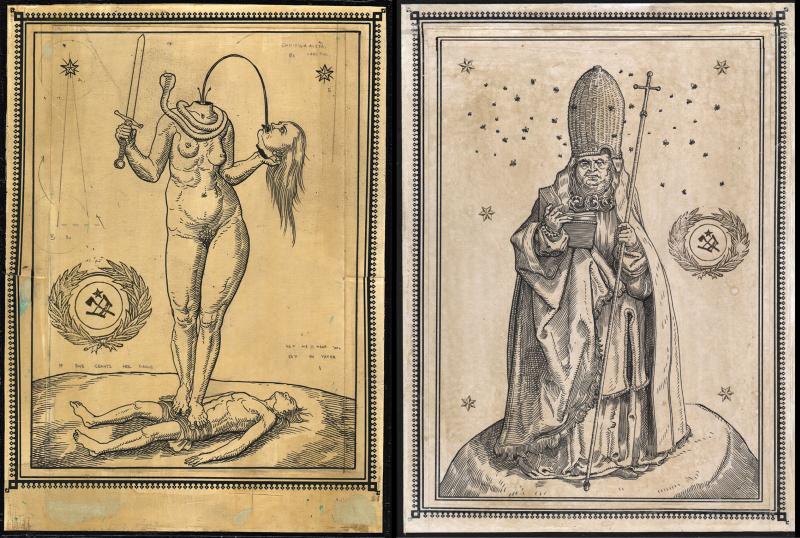

Whore of Babylon and Le Pape by Ravi Zupa.

“He will raise a signal for the nations and will assemble the banished of Israel, and gather the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth.” – Isaiah 11:12

In 1649, a man named Antonio Montezinos arrived in Amsterdam from South America with an amazing story to tell. Montezinos was a crypto-Jew—one of many Jewish people living as Catholics while secretly practicing some Jewish rites after the Spanish Inquisition—who had lived in Spanish-occupied South America for many years as a conquistador. As such, his presence in Spanish South America was a subversion of the colonial regime’s strict Catholicism—Spanish law banned non-Catholic Europeans from its colonies, and this ban was strictly policed by the Inquisition. Montezinos’ Jewish identity had to be well hidden to the point of suppression. Nevertheless, when he arrived before the Amsterdam Jewish community’s high council he used his Hebrew name, Aharon Levi, and spoke to them openly of his travels through the New World. He had returned to Europe a changed man, endowed with new wisdom. We can imagine how he would appear to the Amsterdam Jewish community. What could have happened to this stranger, who had once lived reasonably well among his people’s oppressors? Why would he cast off the prosperity and privilege of that life and make such a clear statement of his Jewishness in a testimony that he knew would circulate throughout Europe? Indeed, his story was tremendous. High up in the mountains of what is now Ecuador, Antonio Montezinos had encountered the descendants of the tribe of Reuben, who sent him back to Europe with a message of hope for the world’s Jews: “They say that the Prophecies do come to passe.”

This was momentous testimony. The tribe of Reuben was one of the 10 tribes of Israel that had been deported by the Assyrians in the eighth century BCE, never to be seen or heard from again. Jews and Christians alike believed that the lost tribes had not only survived that cataclysmic event but would reveal themselves in the run-up to the Messianic age–understood by Jews as the initial appearance of the Messiah and by Christians as the Second Coming of Jesus. Montezinos’s claim was taken up by minds across confessional boundaries, European borders, and even the Atlantic ocean. If these long-awaited days were finally at hand, then everyone would need to begin preparations for the tremendous changes that would shortly be upon them all. These preparations could not be limited to the merely spiritual. The coming of the end times demanded serious geopolitical action, especially in the places where the lost tribes had finally been found.

The Message

“Go ye forth of Babylon, flee ye from the Chaldeans, with a voice of singing declare ye, tell this, utter it even to the end of the earth; say ye, The LORD hath redeemed his servant Jacob.” – Isaiah 48:20

As he later recounted in Amsterdam, Montezinos had come across the alleged remnants of the Reubenites quite by accident and apparently without any inkling that they might still exist. Arrested and thrown into Cartagena’s prison on false charges of trying to convert Catholics to Judaism, Montezinos had the opportunity to reflect on an encounter he had had with Francisco, an Indigenous porter, on one of his earlier expeditions. The journey had been waylaid by a storm that blew over many of the group’s pack mules and damaged the goods they carried. Surveying all they had lost due to both the immediate misfortune of the storm and the ongoing calamity of Spanish colonization, the porters “[confessed] that all that and more grievous punishments were but just, in regard of their many sins…yea that the notorious cruelty used by the Spaniards towards them [the Indigenous people] was sent of God, because they had so ill treated his holy people.” Apparently not realizing that “his holy people” was a fairly obvious reference to Jews, Montezinos, playing his part as a conquistador, chastised the team of porters for speaking so poorly of their colonial rulers. Francisco responded cryptically that “he had not told one half of the miseries and calamities inflicted by a cruel and inhumane people; but they should not go unrevenged, looking for help from an unknown people.” Francisco left open who these “unknown people” were, although it was clear that, whatever their identity, they would reveal themselves to help Indigenous people vanquish their Spanish colonizers.

It was this last line that Montezinos dwelled upon from his prison cell. As he prayed–“Blessed be the name of the Lord, that he has not made me an idolater, a barbarian, a blackamoor, or an Indian,” a bastardized version of the Jewish dawn prayer, which thanks God for not having made the worshipper a slave or a Gentile—the realization hit him: “the Hebrews are Indians.” Fortunately, the Inquisition soon released Montezinos without charges. Reconnecting with Francisco, at whose behest he abandoned his Spanish boots, cloak, sword, and food in favor of Indigenous provisions, Montezinos set off to find the lost tribes. After a week’s travel on foot, they stopped at the banks of a great river and waited for the Reubenites to arrive by canoe.

The Reubenites–described by Montezinos as “somewhat scorched by the sun…comely of body, well accoutred, having ornaments on their feet and legs”–began by reciting the shema, the Jewish profession of faith. They explained to an astonished Montezinos that they were sons of Reuben; that the tribe of Joseph dwelt on an island in the sea; that one day all the lost tribes would reveal themselves, all speaking the same language, following a messenger.

Francisco explained that the lost tribes had made it to the American continents “by the providence of God,” who had also helped them overcome violence from the people already living in the region. These Indigenous peoples became allies and servants to the lost tribes when they recognized that they would benefit greatly by helping the newcomers. Through this cooperation, they learned of the prophecy that, as Francisco puts it, “these sonnes of Israel shall goe out of their habitations, and shall become Lords of all the earth as it was theirs before.” Thus, Montezinos came into knowledge that, he believed, would bring hope and strength to the Jewish diaspora. To share his message, he embarked on the trans-Atlantic voyage to Amsterdam. Montezinos, by no means a humble man, almost certainly traveled in the anticipation that he would be received with interest, if not outright jubilation, by the Jewish community. However, he likely did not realize how his story would become part of a much larger discussion among European Protestants about the Indigenous peoples of America, the Jewish diaspora, and Biblical prophecies about the end of the world.

Christian Stakes in Holy Land

“And he said, ‘Go, and say to this people: “Keep on hearing, but do not understand; keep on seeing, but do not perceive.”’” – Isaiah 6:9

The Amsterdam council recorded Montezinos’ testimony in writing and, as word of this incredible story began to spread among Jews and Christians, requests for more information flooded in. In particular, these questions were addressed to Menasseh ben Israel, a rabbi in the community who had become one of the most prominent Jewish members of the Protestant letter networks that criss-crossed Europe. Menasseh’s Christian interlocutors turned to him for information about Jewish theology, Jewish practice, and the Hebrew language, which they wanted to understand in order to interpret the Hebrew Bible as accurately as possible. Close reading of the Hebrew Bible had been a vital part of Protestant theology and eschatology since Martin Luther: Protestant doctrine held that the Bible was the only infallible authority on proper Christian practice, on the path to personal salvation, and, ultimately, on the end of days. In this way, the scholarly Protestant movement known as Hebraicism provided Jews with an “in” to intellectual spheres that would otherwise have excluded them outright.

News of Montezinos’s testimony eventually reached a Puritan minister named Thomas Thorowgood in London. Thorowgood, originally from Norfolk, had come to the capital in order to publish his much-delayed book, Iewes [Jews] in America, which just so happened to argue the very idea that Montezinos’s testimony seemed to indicate: that the Indigenous peoples in America were, in fact, the lost tribes of Israel. Initially, he had sat on the text, believing its premise to be simply too far-fetched for the English reading public. After all, the lost tribes theory had initially been proposed and ultimately rejected by Spanish colonizers centuries ago. And yet the idea would not leave him be, so he sought and received royal permission in 1648 to bring the book to print, though the execution of King Charles I postponed publication and forced Thorowgood to rededicate the book to the “Knights and Gentlemen of Norfolk” rather than to the recently beheaded sovereign. All told, Thorowgood arrived in London in 1649, manuscript in hand, ready to finish the work he had begun so long ago—if for no other reason, perhaps, than to finally have it over with.

When he learned of Montezinos’s discovery, Thorowgood was surely flabbergasted. He had fully expected his book to remain relatively obscure, catching the interest of only those truly invested in the lost tribes theory. Yet here was someone, come from very far away, who corroborated his theory! Moreover, Montezinos was an adherent of Judaism and would unquestionably know a true Israelite from a false one. In a fervently Protestant milieu where such things mattered greatly, it must have seemed like a providential sign. Through mutual contacts, he immediately reached out to Menasseh for a copy of the testimony.

Lost Tribes Rediscovered

“In that day the LORD with his hard and great and strong sword will punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent, Leviathan the twisting serpent, and he will slay the dragon that is in the sea.” – Isaiah 27:1

Unfortunately, Menasseh, beset with letters from all over Europe, took much longer to respond to the request than Thorowgood had expected. The preacher returned home to Norfolk, weary and homesick after his long stay in London, and left it to friends to oversee the final stages of publication. He never had the chance to read either Montezinos’s account or Menasseh’s letter vouching for its veracity before Iewes in America appeared on the market with both documents included. If he had, he would have noted several major differences between his version of the lost tribes theory and the one described by Montezinos and corroborated by Menasseh. Most notably, while Montezinos drew a distinction between the Reubenites and their Indigenous allies, Thorowgood believed all Indigenous peoples in the Americas to be lost Israelites.

The differences between the two versions can be chalked up to the different positions and aims of the theorizers. Montezinos, a crypto-Jew, wanted to bring a message of hope and liberation to the Jews of Europe. His story tells of a small but providentially empowered group of lost Israelites, with more, such as the tribe of Joseph, to be found in other parts of the Americas. Crucially, this little host of American Jews had the allyship and assistance of the truly original inhabitants of the Americas. As Francisco, Montezinos’s guide, pledges, “After we have finished a business which we have with the wicked Spaniards, we will bring you out of bondage, by God’s help.” This matches up with broader trends in Jewish thought at the time. Jewish intellectuals like Menasseh assumed that Jews were a minority everywhere they lived and believed that only when Jews were scattered all across the earth, as Isaiah 11:11-12 specifies, would they retake the Holy Land and usher in a Messianic age. This future reign of the Messiah was not understood as an end to history but an epoch where Jews would be governed in accordance with Biblical law as one nation, albeit the most blessed and prosperous one, among many.

Thorowgood, a Puritan minister, had a very different perspective on the meaning of prophecy and the Biblical timeline. He believed that the end of days would feature the Jewish conquest of the Holy Land, a cataclysmic battle with the forces of the anti-Christ (variously defined as Catholicism, the Ottoman Empire, or both), the conversion of the Jews, and the return of Jesus Christ. Thorowgood was concerned with Jewish restoration only for Christian eschatological ends, which included the disappearance of Jews as a distinct religious community. Thus it stands to reason that his lost tribes theory makes no distinction between Israelites and other inhabitants of the Americas; for him, these peoples were just allies in the coming war and future converts to Christianity.

Whereas Montezinos renounced his conquistador identity to embrace a fully Jewish one, Thorowgood’s writing was directly aligned with English colonial priorities. Montezinos had to give up the trappings of Spanish imperialism to meet his brethren; it was only by shedding his external Spanishness, including his Spanish name, that Montezinos won Francisco’s trust. Once he had done so, he was made privy to a secret plan to defeat the cruel colonizers and liberate the world’s Jews from their oppressors. Thorowgood, on the other hand, carried a deep emotional investment in the English imperial project. Much of Iewes in America is dedicated to the hard work and missionizing zeal of the “Novangles,” a portmanteau from the Latin nova and Anglia that he used for the New Englanders. Thorowgood also drew heavily from missionary reports from New England for evidence that the lost tribes dwelt in America.

While the lost tribes theory was not altogether novel to the English reading public, it was considered somewhat passé. A relic of early Spanish exploration in the 15th and 16th centuries, it had fallen by the wayside of intellectual exchange. Thorowgood was one of the first authors to revive the theory in the mid-17th century, with a distinctly English Protestant perspective. Large parts of his case follow the contours of other lost tribes theories and borrow examples from previous texts. He cites observations, both by Novangles and earlier colonists, that Indigenous peoples in New England speak a language similar to Hebrew and separate menstruants from the rest of the community. In a striking episode, he retells the story of a whale hunt first told by José de Acosta in Historia natural y moral (1590), where Indigenous Mexicans

[lead] a Whale, as big as a mountaine, with a cord, and vanquishing him in this manner; by the help of their Canoes or little Boats, they come neare to the broad side of that huge creature, and with great dexterity leape upon his necke... they kill the Whale, cut his flesh in pieces, they dry it, and make use of it for food…thus plainly verifying the expression, Psal. 74 14.The verse he references reads, “It was you who crushed the heads of Leviathan and gave it as food to the creatures of the desert.” For Thorowgood, the whale hunt in Mexico illustrated the truth of God’s promises: God fed the people in the wilderness on the flesh of a great monster. It was also prophesized that God would slay the Leviathan (albeit in the form of a snake rather than a whale) directly before the end times. Thorowgood’s argument takes as its starting point the supposition that Jews and Indigenous Americans share a common Israelite heritage; his project is not to arrive at that conclusion from observation but to give reasons why his supposition is likely. Thorowgood uses the Bible in this way to promote the English colonial expansion, with its attendant processes of Christianization and progress towards the Second Coming.

Thorowgood elides any distinction between different Indigenous nations and different regions of the Americas, treating the inhabitants of Mexico, Brazil, and New England as one nation. For him, the widespread use of canoes across the Americas and the consumption of corn as a staple of Indigenous diets proved that all these peoples, despite whatever external difference they might display, were in fact one nation: the remnants of Ancient Israel, who had adapted to the vast array of American landscapes by making use of the same technologies. Any variation in cultural practice and appearance could be chalked up to years of diaspora or to distinctions between the original 10 lost tribes.

Flesh Eating Foretold

“And in that day a great trumpet will be blown, and those who were lost in the land of Assyria and those who were driven out to the land of Egypt will come and worship the LORD on the holy mountain at Jerusalem.” – Isaiah 27:13

While Thorowgood initially seems to adhere closely to typical arguments for the lost tribe theory, he makes one claim that is, to my knowledge, unique among theorists: that the Indigenous peoples in the Americas had to be Judaic because they were cannibals. Thorowgood acknowledges the apparent absurdity of his conjecture: “This which followeth next, at first sight, will appeare a Paradox rather than a Probability…. What an inference may this seem to bee; there bee Carybes, Caniballs, and Man-eaters among them, therefore they be Jewish?” Nonetheless, he proceeds with his case. Thorowgood presents several biblical prophecies1 that predict that the children of Israel will, in times of calamity, resort to cannibalism. he specific prophecy that applies to Indigneous peoples in America is Ezekiel 5:9-10:

And because of your abominations I will do with you what I have never yet done, and the like of which I will never do again. Therefore fathers shall eat their sons in the midst of you, and sons shall eat their fathers; and I will execute judgements on you, and any of you who survive I will scatter to all the winds.In Thorowgood’s reading, two other prophecies of cannibalism have already come to pass in the biblical past when women ate their children during a famine in Samaria and Nebuchadnezzar’s siege of Jerusalem respectively. (This, like the whale hunt, proves the truth of God’s promises: the fulfillment of these prophecies within the Bible’s internal narrative represents a further guarantee that all the Bible’s predictions will come to pass.)

Only the prophecy in Ezekiel, Thorowgood writes, has not yet come true. In Samaria and Jerusalem, women had devoured their children out of desperation, but Ezekiel specifies that fathers and sons—male relations—would eat one another. According to Thorowgood, there is no evidence that an event like the one specified in Ezekiel has come to pass except in the Americas, where, he asserts, “if they want the flesh of Foes and Forraigners, they eate then one another, even their owne kinred & allies.” Allegedly, the desire for human flesh was so great among the Indigenous peoples in the Americas that sons and fathers would happily consume one another if supplies ran low.

Understanding Cannibals

“‘To whom will he teach knowledge, and to whom will he explain the message? Those who are weaned from the milk, those taken from the breast? For it is precept upon precept, precept upon precept, line upon line, line upon line, here a little, there a little.’” – Isaiah 28:9-10

Thorowgood’s unusual contention that Indigenous cannibalism was a fulfilment of biblical prophecy built upon centuries of European discussion about who practiced cannibalism, what it signified, and what should be done about it. It is widely understood that “cannibal” is etymologically linked to “Carib,” the name given by Spanish colonizers to a group of Indigenous people in the Caribbean who were accused of eating people. European readers closely followed reports of cannibalism in the Americas, and the majority of them took cannibalism as a sign of degradation, inhumanity, and heathen religion. The narrative coming out of the Spanish Atlantic emphasized the danger these un-Christianized cannibals posed not only to colonizers but also to their Indigenous neighbours, who were characterized as gentle, childlike, and prepared to accept the gospel. The threat of cannibalism could be met and overcome by missionary zeal; in effect, Indigenous peoples could be lumped into two groups, those meek enough to come to Christ quickly and the cannibals, who needed to be converted by force in order to protect the first group.

The question of whether coerced conversion was a legitimate way of enforcing Catholic mores and imperial order in the Americas came to a head at the Valladolid debate of 1550-1. Bartolomé de las Casas, Bishop of Chiapas, Mexico, argued passionately that the Indigenous peoples of the Americas were free and could not be compelled into the lap of the Church by violence. He acknowledged that the practice of human sacrifice was common among these peoples but contended that, nonetheless, they would have to come to Christianity of their own accord. In fact, Las Casas took alleged ritual human sacrifice as evidence that Indigenous people were capable of tremendous piety and zeal, which would be useful to the Church after their eventual freely chosen conversion. His opponent, the theologian Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, reasoned that these “uncivilized” practices were a violation of natural law and an affront to humanity and should, therefore, be extinguished by any means necessary.

Early modern discourse around cannibalism was not particularly interested in whether cannibalism actually occurred in the Americas—all parties agreed that it certainly did—but rather how it should be understood. In the 16th century, when the New World was still very new to Europeans, stories of Indigenous cannibalism abounded. A German adventurer named Hans Staden published a widely circulated account of Indigenous Brazilian anthropophagy in 1557. Drawing on Staden’s account, the late-16th-century essayist Michel de Montaigne used his piece “Of Cannibals” to make the case that cannibals in South America were not uncivilized monsters but rather demonstrated martial virtues like loyalty and bravery.2 Montaigne writes that, despite the apparent brutality of cannibalism, Indigenous people live well and honestly:

Their disputes are not for the conquest of new lands, for these they already possess are so fruitful by nature, as to supply them without labor or concern, with all things necessary, in such abundance that they have no need to enlarge their borders. And they are, moreover, happy in this, that they only covet so much as their natural necessities require: all beyond that is superfluous to them.Montaigne describes Indigenous people executing and then eating their prisoners of war, “not…as some think, for nourishment, …but as a representation of an extreme revenge.” He later compares this treatment favourably to European tortures, writing, “I conceive there is more barbarity in eating a man alive, than when he is dead; in tearing a body limb from limb by racks and torments, that is yet in perfect sense; in roasting it by degrees… than to roast and eat him after he is dead.” For Montaigne, attempts to drive out cannibalism abroad just revealed the violence, greed, and arrogance of Europeans.

While the term “cannibal” is uniquely linked to colonialism and the European encounter with the so-called New World, accusations of people-eating were far, far older. We have already seen several instances where the Bible describes it, albeit as an outcome of divine punishment. Ancient Greek sources like Homer and Herodotus described fearsome foreign cultures feasting on human flesh and gave us a word for the behavior: anthropophagy, from anthropos (ἄνθρωπος), human, and phagos (φᾰ́γος), glutton. The connotation of gluttony, of greed, of bloodlust, came to the fore with the rise of the blood libel, a fabricated narrative popular in the medieval and early modern eras that accused Jews of consuming the blood of Christians, especially Christian children, for ritual purposes. There are many versions of this accusation: in some, Jews crucify Christians in a mockery of Christ; in others, victims are circumcised; in still others, the blood is used to make matzah, the unleavened Passover bread. The beats of the story, however, are almost always the same: interrogation under torture, conversion under duress, execution at the stake or the gallows. In this manner, entire Jewish communities were snuffed out, with most of the men dead and the survivors—women and children, mostly—sent into exile.

The blood libel was a, if not the, dominant accusation of anthropophagy in Europe–and yet, remarkably, Thorowgood does not bring it up in his book. I do not want to suggest that Thorowgood was some great friend to Jews. Instead, his reasons here have more to do with philosemitism and Protestant beliefs. Whereas the early modern antisemite wanted Jews exterminated through violence, the philosemite wanted Jews to disappear via conversion. Philosemitism is therefore not the opposite of antisemitism; they are two sides of the same coin. For Thorowgood and his ilk, Jews were not worthy members of society in and of themselves; they were useful soldiers for the final confrontation with the anti-Christ and the return of Christ. In fact, Thorowgood reaches for antisemitic tropes in describing why God would have allowed the Israelites, his chosen people, to devolve into cannibalism: “They crucified their Saviour, and made him their enemy and avenger.” Thorowgood only rejects the idea that all Jews ritually consume Christian bodies because it has to be a previously unseen atrocity in order for the prophecy in Ezekiel 5:9-10 to be true.

In the same vein, Thorowgood’s criticism of Spanish colonial rule was rooted in concern for the expansionism and capitalism of the Massachusetts Bay Colony rather than the well-being of Indigenous people. He brings up atrocities committed by the Spanish in his chapter on cannibalism, recounting how

their owne Bishop Bartholomeus de las Casas writes, how they tooke Indians 10000, sometimes 20000 abroad with them in their Forragings, and gave them no manner of food to sustaine them, but the Flesh of other Indians taken in Warre, and so Christian-Spaniards set up a shambles of mans flesh in their Army.For the Indigenous inhabitants of the Americas, who, according to Thorowgood, were already accustomed to eating human flesh, “this was most hideous and most barbarous inhumanity” and certainly qualified as the prophetic assertion in Ezekiel that “I will do with you what I have never yet done.” Accounts of Spanish colonial cruelty were taken by English Puritans as evidence that Catholicism would reveal itself as the anti-Christ in the end of days, which meant that it was necessary for England to expand its reach into North America before Catholic countries could take their opportunity to do so. There were, of course, also immediate practical dimensions to Anglo-Spanish colonial rivalry: Spain had become enormously wealthy off its colonial exploits, and England wanted to do the same, both for its own ends and to pre-empt other nations. This more practical element is not obviously present in Thorowgood’s writing, but his inclusion of Spanish colonial violence clearly bolsters both cases for English colonial expansion and profit.

New Englanders and Ancient Israelites

“And behold, joy and gladness, killing oxen and slaughtering sheep, eating flesh and drinking wine. Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” – Isaiah 22:13

It is no accident that the final push to publish Iewes in America came from missionaries in continental Europe and the Massachusetts Bay Colony: the colony had always oriented itself towards Christianization. Its charter, issued by King Charles I in 1629, permits the new colonists to wynn and incite the Natives of Country, to the Knowledg and Obedience of the onlie true God and Savior of Mankinde, and the Christian Fayth, which in our Royall Intention, and the Adventurers free Profession, is the principall Ende of this Plantation. The charter not only sanctions missionizing but makes it the explicit goal of the colony. The use of the word “Plantation” brings a second objective into focus as well: the Massachusetts Bay Colony was meant to be a productive and lucrative resource-extraction venture, both to furnish the metropole with the commodities it could not produce on its own, such as fur and timber, and to sustain expanding English influence in the Atlantic World, most importantly further afield in North America. All of this was made manifest in the colony’s seal, which featured an Indigenous man, long-haired and naked behind strategically placed shrubs, carrying a bow and arrow and begging colonists to “come over and help us.” In this context, “help” referred both to Christianization and to English “assistance” in making the land profitable according to English notions of land-use.

Seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in use 1629-1686. Accessed via WikimediaThorowgood’s version of the lost tribes theory, including and especially his conjecture about cannibalism, fits this mission. Indigenous peoples in the Americas, he argues, are not only remnants of the lost tribes of Israel but have truly fallen away from their former Judaic faith and culture. This argument holds within it a second one that presupposes that Indigenous peoples could no longer be accurately described as Jewish because of that “decline.” Puritans like Thorowgood expected that the Second Coming and the end of days would be prefigured by, among other events, the conversion of Jews to Christianity. To that end, it was believed that Jews should not be subjected to a concerted missionary program because their ultimate conversion would occur through the spontaneous recognition of Jesus Christ as the Messiah. Indigenous peoples in the Americas, however, needed to be converted to Christianity to properly appreciate the cosmic plan in the first place. Moreover, Thorowgood notes that unlike European Jews, who have heard the Christian gospel and rejected it, Indigenous people had not previously come into the knowledge that Christianity existed except by the missionizing efforts of colonists. Iewes in America therefore legitimizes the Christianizing mission in New England. Even if this mission should fail or only succeed partially, the logic went, the very fact that English settlers were pushing Christianity on Indigenous people in and around Massachusetts Bay meant that they, too, were fulfilling biblical promises.

Who Is a Cannibal?

“I will put in the wilderness the cedar, the acacia, the myrtle, and the olive. I will set in the desert the cypress, the plane and the pine together, that they may see and know, may consider and understand together, that the hand of the LORD has done this, the Holy One of Israel has created it.” – Isaiah 41:19-20

Writing about cannibalism is a challenge; as others have noted, cannibalism is not a neutral term, and to relate that a particular group practices cannibalism is not merely a descriptive claim. Even if accurate, such allegations inevitably entail a moral dimension. Claims of cannibalism always flow from one group towards another and carry with them deep and destructive normative distinctions: civilized vs. uncivilized, in vs. out. We see this in the very origins of the word–indeed, Thorowgood uses the word “Carybe” as a synonym for cannibal. In light of this, it is difficult to make determinations about whether an individual or population historically consumed human bodies based on the usual archival sources that historians rely on. These normative distinctions around the accusation of cannibalism mediate and distort primary source accounts in even the best-case scenario. Often, it is impossible to tell which European claims of cannibalism are outright fabrications. At the same time, to automatically assume that any European claims of Indigenous cannibalism are entirely fictitious reproduces the same normative judgments, casting Indigenous peoples as “Noble Savages” who are purer, more innocent, and more moral (according to a Eurocentric conception of morality) than the colonizers who would resort to cruel lies to discredit them.

Thorowgood never lived in the colonies, never even ventured there. When he described the Indigenous population as cannibals he was resting on older reports, largely from Spanish explorers, and simply took for granted that these accounts were both factual and applicable to New England. Actual reports from New Englanders differed from this assumption. In the 1630s, descriptions of the colony’s early days and the 1636-1638 Pequot War recounted that the Algonquian nations who lived nearest to the colonists–most prominently, the Narragansetts, Wampanoags, Massachusett, Pequots, and Mohegans–feared the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka (Mohawk), who allegedly used cannibalism as a weapon of war. These allegations are highly mediated. It is unclear if they are based on observations made by the English writers; it is likely that, to some extent, descriptions of cannibalism perpetrated by the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka were provided by the colonists’ Indigenous neighbours, who may have exaggerated the brutality of conflict with the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka in order to discourage English settlers from establishing relationships with them.3 Nevertheless, even if we take these accounts at face value, what colonists describe is nothing like Thorowgood’s assertion that fathers and sons devoured one another, openly and in public, out of lust for human flesh.

To Devour

“Your country lies desolate; your cities are burned with fire; in your very presence foreigners devour your land; it is desolate, as overthrown by foreigners.” – Isaiah 1:7.

In From Communion to Cannibalism, Maggie Kilgour proposes a metaphorical dimension to cannibalism that relates it to desire. For Kilgour, cannibalism is most clearly about incorporating external things into the self. Through this desire for incorporation, she links cannibalism to broader human concerns including love and sex, hunger and eating, knowledge and reading. By applying an inside/outside or self/other dichotomy, Kilgour reveals her metaphorical cannibal’s desire for the unknown to become not only knowable, or even known, but familiar, a part of themselves.

In the 17th century, this metaphorical cannibal arrived on the shores of Algonquian territory in the form of the literal English settler. Having butchered their own lands and body politic, as Kilgour puts it, first through enclosure and then through the “intestinal” English Civil War, colonists sought to do the same in North America. The English process of parceling up and selling off land served to make land purchasable, commodified, digestible. The same can be said of the division of people into clearly identifiable factions in the context of the English Civil War. In New England, our metaphorical cannibals not only replicated this pattern but expanded it. But before the land and its people could be devoured, they had to be deboned. Settlers deliberately ignored land use practices by the Indigenous nations of the region, such as the Narragansetts’ crop farming and conservation of beaver stocks and tidal flats, because they did not conform to an English conception of cultivation—or at least the new, enclosed conception that had no use for the commons—which rooted itself in permanent land ownership, fencing, and domesticated farm animals. Having invalidated Indigenous ways of life, colonists from England could go about consuming and converting land into English territory, resources into commodities, and Indigenous people into Christians.

Kilgour’s understanding of cannibalism as a kind of overwhelming and transformative desire for unity touches on Hegelian dialectic, in which both the subject and object relate in such a way that each becomes the other even as each becomes itself. But unlike the sublation of Hegelian dialectic, cannibalism-as-colonialism is a true negation. There is no reciprocity here: you cannot devour and be devoured in return, although the colonists’ fear that the tables would be turned on them and they could become the eaten rather than the eaters animated—and continues to animate—settler ideology.

Thorowgood’s argument replicates this one-sided consumption and digestion. His conflation of all Indigenous peoples takes a diversity of nations spanning vast continents and makes them one easily digestible group composed entirely of cannibals. And he transforms that homogenous, undifferentiated group, in all its otherness, into a people already known to him: Jews. The fact that Thorowgood knew almost nothing about Jews was no impediment to his cannibalistic appetite–he had already consumed other sources on their customs and practices and, most importantly, he had devoured the Hebrew Bible. It is significant that the verses Thorowgood uses to support his cannibal conjecture are all from his Old Testament. By making use of Ezekiel, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy, he asserts his rightful ownership as a Christian over these texts, co-opting Jewish religion and tradition to support colonial expansion into North America.

It appears that Thorowgood has a foil in Montezinos. Thorowgood drapes himself in prophecy to push English expansion; Montezinos uses it to oppose Spanish colonial cruelty. Thorowgood authored his own interpretation of the Bible; Montezinos presented himself only as the messenger of truth. Thorowgood coveted places that are not his, places he never visited; Montezinos wanted only to return to his ancestral homeland. Thorowgood salivated at the prospect of more land, more souls, more commodities; Montezinos rid himself of his colonial identity, revealing himself as a man of the diaspora rather than a colonizing force. Whatever Thorowgood devours, Montezinos, it seems, spits out. In one corner, the glutton, in the other the regurgitator who can no longer stomach what he has been fed.

And yet, this is far too simple. In telling the story this way, we elide the fact that Montezinos, too, was a cannibal. When confronted with a people he didn’t know and couldn’t understand, he digested them through half-remembered prayers and prophecies so that they were not only comprehensible but a beacon for his own difficult life. The story he told to the Amsterdam Jewish community was compelling, profound, and hopeful. But it wasn’t true. All the beauty and meaning of his story rested on the shoulders of Indigenous people who were never given an opportunity to weigh in.

The lost tribes theory landed on the Indigenous peoples of the Americas in much the way European colonizers did, without any appreciation for the complexity of their cultures or the distinctions between them. Evidence of its inaccuracy was obvious and easily available—for instance, it became increasingly apparent that no Indigenous languages in the Americas were Semitic—but the notion proved surprisingly tenacious. It is not difficult to see why: it explained an Other in a way that collapsed nuance, sanctioned genocidal colonialism, and made that Other easy to digest. Today the lost tribes theory survives as a historical curiosity, toothless and withered. And yet prophecy continues to be used as justification for ongoing colonialism, unsolicited missionizing, and even government policy. Thomas Thorowgood’s alleged cannibals-cum-Jews might be a long-gone figment, but his intellectual heirs are very real and very, very hungry.

1 Lev. 26:29 reads, “You shall eat the flesh of your sons, and you shall eat the flesh of your daughters.” Deut. 28:53 reads, “And you shall eat the offspring of your own body, the flesh of your sons and daughters, whom the LORD your God has given you, in the siege and in the distress with which your enemies shall distress you.”

2 Modern scholars suspect that both these texts influenced the semi-human Caliban in Shakespeare’s Tempest, whose name is likely linked etymologically to the word “cannibal.”

3 If so, this strategy ultimately came to nought when the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka made common cause with the New Englanders to devastate an alliance of Algonquian nations in Metacom’s War, which lasted from 1675-1678.