SER

Ayahuasca, the Eye, and the Ashram

ISSUE 96 | PROPHECIES | JAN 2021

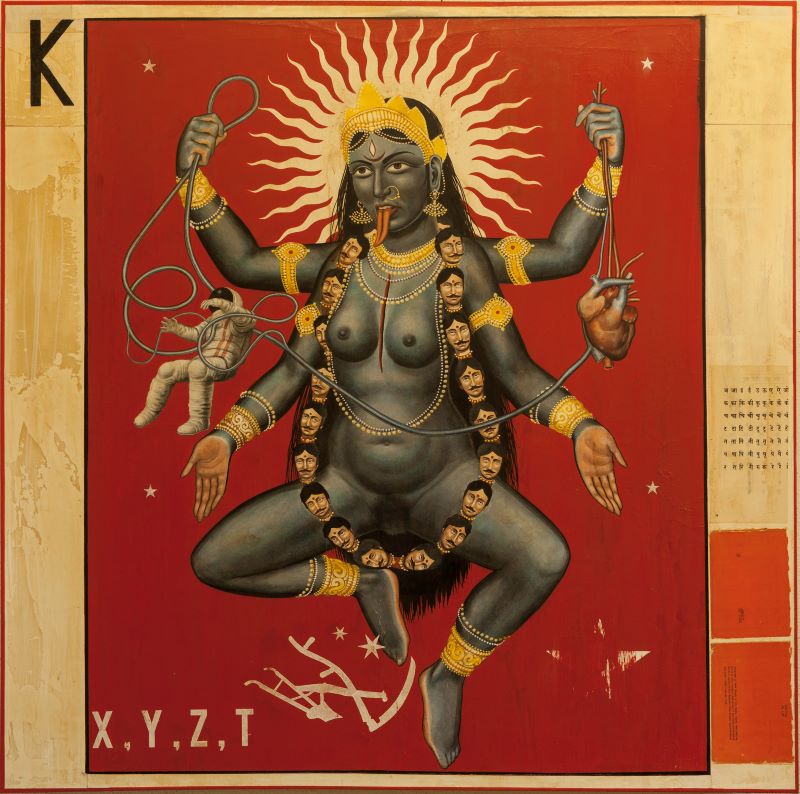

Coordinates by Ravi Zupa.

When I first saw the swami, he passed like a storm cloud across the periphery of my consciousness. He must’ve been dressed all in yellow, but I hardly registered his image. That was before he became a swami, wearing only orange. I had just arrived at the ashram, and I was tightly hugging my soon-to-be ex-partner goodbye. A few days later, after the training began, I sat in class and stared at him as he delivered a teaching. His gaze met mine, and calmly stayed, until it felt like he accidentally fell into a pool, and promptly jumped back out, looking away. He told us the story of sage Narada, who asks Lord Krishna to share the secret of maya, this world of illusion. Krishna tells Narada to fetch him a glass of water. Narada runs to the nearest village, and promptly falls in love with the woman at the well, after just one look into her perfect eyes. Years pass; they start a family and blissfully grow old together. Then a flood comes, destroying her, their home, and the lives of the entire family. Heart shattered, completely alone, Narada falls to his knees and cries out to the Lord. And there stands Krishna, asking after his glass of water.

If I had understood the depth of his fear then, I might have saved our hearts some trouble. Instead, I thought about the story’s striking parallels to the Book of Job, both of us Jews, and asked him for its source. He directed me to the Puranas, avoiding my gaze. Late that night, in the library, I found the story of Shiva and Parvati: the Master Yogi surrounded by an entourage of demons and ghouls, and the Daughter of the Mountain enacting ascetic feats so powerful that Shiva cannot look away, hard as he tries. I loved that Parvati’s commitment to divine connection could look terrifying, yet bring love—a love stronger than any ascetic vow. I felt suddenly soothed in my nightly pattern: walking the ashram grounds like a ghost, sobbing and writhing on the corners of the land, screaming alone into the darkness, long after the others went to sleep.

On my birthday that year, the mirror on my door crashed down in the morning; I awoke suddenly from a dream. I was at the ashram, about to leave, running towards the forest to say goodbye to Goddess Durga at her shrine, but the swami was standing at the edge of the trees. I stopped. I would only have time to say goodbye to one of them. He was very old, but when I looked into his eyes, he was the same. Time stopped, and there was only that, the mutually held gaze overtaking the universe.

* * *

My mother told me that when I was a child, sometime before my father left—I had to have been less than four—there was a long metal pole lying in the living room. It was his, and she told him to put it away, for the safety of the children. He didn’t. Of course I found it, and put it straight into my eye. I had to go to the hospital, I scratched it badly, I don’t remember that part, they thought I might lose my vision, but I remember the eye patch I wore afterwards, and I didn’t give two shits about it, I was a happy pirate.

That winter, before returning to the ashram, I spent two nights with my mother in a rented room in the middle of the city. Before I left, in the middle of the night, the giant “A” hanging on the wall above our bed fell on her head. She sobbed and sobbed while I held her and patted her head and told her it was okay. We stayed like that for a long time, and I thought about the dream I’d just had.

I was in a small dark shop filled with dark tapestries richly woven with electric colors, like Shipibo kené, abstract embroideries of Amazonian plant communications. It was at least a few hundred years in the past, and I had recently entered a high-society marriage with a man I didn’t love. I wore dark drab colors, like a woman mourning her own death. I felt so old. He walked in, golden warrior, skin glowing like the sun. The dictates of propriety forbade him from looking at me, but our hearts knew each other well. I went back to the tapestries, and heard him giggle with the shop girl, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed young woman with matching electric blue-green lines tattooed across her face. Her sweet laughter made me feel even older. Sitting there in the dark, holding my mother, with her childish tears and her anxious need for a man and a mother, I vowed to never settle for anything less than love, even if that meant I would be alone forever.

When I showed up at the ashram, she was there. A young woman with long blonde hair, bright blue eyes, and a sweet starry-eyed connection with the swami. She always sat right in front of him in the temple, but when I came to sit nearby, she ran away. One day we ended up in a car together, just the three of us, after visiting a nearby shop, and I felt something come full circle. As we exited the car, I asked him if we could talk. I took us closer to the edge of the forest, closer to the water, and told him, asked him, about the energy between us. His eyes turned to mirrors, impenetrable, locked. Words crawled slowly from his mouth; the man that preached the light of awareness claimed he had none, and then he tentatively asked if the energy was good . . . or bad. I laughed. Both, I said. He said okay, still frightened, and gave me a book of stories about how great meditation masters die. It was the perfect gift, and I was furious. In exchange for his denial, I ignored him for days, and when I left, he was suddenly leaving too, and we both climbed the bus back to the city, while his attendant did a double take as she watched us go, suddenly seeing something she was not meant to. It was the only time we ever had alone together, side by side, and the sun streamed gently through the windows and soft clouds, caressing us the whole way.

* * *

After learning that I had been incested by my father, I sought out the medicine: ayahuasca, the vine of the dead, grandmother snake of the Amazon. I didn’t want to return to the ashram, the swami’s inability to speak openly had soured me, but the medicine hit me hard, and I needed a place to recover. I hungered to enter savasana, corpse pose, but could hardly touch it, until a yoga nidra session where I fell into savasana like a deep dark well, and re-emerged suddenly, sobbing, gasping for air, unsure of where I’d been. On my last day, he stopped and stood behind me while talking to someone, so that I couldn’t move without touching him. I was so angry I left without a word.

I continued on the medicine path, elaborate maps of family trauma unfolding as I slogged through the mud, plant ceremony after plant ceremony. I began to understand how the medicine speaks to me. Terrifying, nauseating, dazzling visions—electrified colors, intricate patterns—mean surgery. I surrender, the visions vanish, and surgery comes. It is excruciating: something somewhere deep inside unclenches and searing pain flashes through me like lightning. I vomit, I cry, I am flooded with memories. Then the storm subsides. My body is new, my heart at rest.

I returned to the ashram a year later, stronger, fully believing that the energy between the swami and me had fallen away. In the pre-dawn darkness I prepared for Vana Durga puja, a fire ceremony in honor of the Forest Goddess Warrior at her shrine. I dressed in my Shipibo embroidery, honoring Vana Durga as part of the Plant Queendom, for she, too, speaks through the trees. I arrived at the shrine in step with the brahmanical priest, and, annoyed at my timing, he sent me away to help the swami and the others. We gathered the space together. I prayed fiercely to Vana Durga-Ayahuasca, chanting with the group as the light of dawn grew. At the close of ceremony, we all lined up in front of the swami to receive the seal of vibhuti, sacred ash, upon our foreheads. As I came forward, I closed my eyes so as not to frighten him, and turned my face to him to receive. I felt his fingers brush my hair from my forehead, so tenderly, freezing at the end of the gesture, as if realizing that wasn’t supposed to happen. Then he placed his ash finger on my third eye and it reverberated through my entire body. In crow pose later that morning, my strength suddenly gave out, and I collapsed in tears, overcome with grief. That afternoon, a man I had recently been dating called me to break things off, inexplicably. I screamed as I vacuumed the massage studio.

A few weeks later I traveled from the ashram into another ayahuasca ceremony. I walked up a staircase towards the door, the colors around me warm and cozy, harbingers of home, and right as I approached the door, blood streamed down from top to bottom, oozing from the crack beneath. Murder, but whose? Then I watched him die, over and over. Sometimes I would die too; it was always one of us. He would go into battle, and I would find his corpse after the fall. I watched myself perform sati, the now-outlawed Hindu practice of the widow immolating herself on her husband’s funeral pyre, proving her purity. I entered the fire, and whispered to myself, incredulous in the dark: “How many times did I die for you?” He died for me too. I saw the other side of all those deaths: our spirits spinning together in the upper realms with a light so powerful it could shatter and rebuild worlds. The ashram hills beckoned me; the medicine said it was time to leave my current life and go there: we had work to do.

In the Ramayana, Lord Rama is exiled to the forest, and his wife Sita, born of the blood of sages, follows him. The demon Ravana desires her, and abducts her to his kingdom. After Rama rescues Sita, she completes a trial by fire to prove her purity. They rule Rama’s kingdom, but the talk of the town sows seeds of doubt in Rama, and he orders his brother to take his pregnant wife to the forest and abandon her there. When Rama encounters her and their twin sons years later, he asks her to return with him. She asks Mother Earth to have mercy on her, and the earth splits open and swallows her.

* * *

A few days before I dipped back into the ashram that winter, ready to share my plans to stay more permanently, scandal broke. The dead guru that watched us from the walls and settled on our lips in daily prayer had raped his personal assistant for years. On the last full moon of the year, she finally went public. Her spiritual father would climb into bed with her at night, and in utter confusion, after years of service, she surrendered, again and again, and even stood by as his caretaker unto death. I was certain that reckoning and reform was on the way—this place of virtue and healing just needed a little truth adjustment, and weren’t we right on time? The night I arrived, I put my kindest face on and tried to speak to the director, but he pointed at his dinner and said he was trying to eat. The pictures stayed on the wall and the guru’s name on everyone’s lips. I refused to say the name, and went looking for whispers of those that agreed.

When I finally deliberated openly with some staff, a kind hardworking woman said she was sure he didn’t do it, he was too old—sixty! And besides, she’d heard that his accuser was raped as a child, so she had to be making it up. I caught my breath and spoke: people who are sexually abused as children often re-experience that abuse throughout their lives, our energy already perforated, creating a sort of magnet. In our prayers the following morning, I sat in front of the director and cried in his face. He said that some of us may not agree, but he didn’t say about what, and he looked at me. I stared back and nodded. He continued to speak abstractly about people making up stories in their heads, holding on to dramas and illusions, and covering up the light and truth of reality. I listened as he twisted wisdom into a weapon. That night, when the swami chanted the guru’s name, we all fell silent, and I felt like I’d won the lottery. He was embarrassed, and tried to save face with a teaching about the light of the gurus, and I stormed out of the meditation hall the moment he finished. The next morning, he chanted to Lord Rama, still worshipped today as a paragon of virtue, and I thought I might vomit, until he got to the line about Sita, and as he sang her name, I heard the tears in his voice, and felt the enormous sorrow in his heart, and in mine.

In our staff meeting that day, everyone ripped into the director, telling him how exploited they felt under his rule, how disrespectful and insulting he had been with them on a regular basis. I told him that gaslighting is real, that telling rape survivors that we are making up a story in our heads doesn’t work, it only drives the wedge deeper. I told them that I was planning to come to stay, but needed to know that I was safe. The swami looked straight at me as he enumerated all the ways that he thought order could be restored, and I felt fully equipped to help enact it all. We left triumphant, feeling like the winds had shifted and we could almost see a sunny shore in the distance, but relief was short-lived. Within a few hours, I discovered that another woman was in love with the swami, too. She saw how he addressed me, and she was livid. I asked, concerned, rape still on my mind, if anything had happened. She said that she wasted her time all these years here, and that I was young and pretty enough, he would bat his pretty eyes at me too. The next day, a bunch of staff people quit, including her and the woman that had thought the guru was too old for sex. The scorned lover tore down the main temple image of the guru. I knew her loud act would be swiftly reversed, but celebrated her boldness, and seized the opportunity to remove and eliminate every single image of the guru in the guest bedrooms, for I could scarcely stand the idea of his lecherous gaze on all those women at night, thirsting from beyond the veil.

* * *

In one of my ceremonies, ayahuasca reminded me of something my brother had shared, about walking into my room in the middle of the night, and seeing me rise up suddenly with my eyes open, turning towards him and staring straight at him in the dark, my eyes wide. He tried to speak to me, thinking I was awake, but I wasn’t, and he left in fear. Ayahuasca showed me how I did that in my sleep, primed and ready to pierce intruders with my eyes, and asked me why he had come, and asked me why I learned how to do that. I remembered a dream in which I was eating shit out of the underwear of my family, and at the same time, my mouth was sewn shut. Suddenly, I was a child again, and I was stuck underneath a giant sieve, with shit pouring down, the shit of my family and all their ancestral lines, and I had to hold it all, or transmute it. I ran out of the ceremony room, and raged in circles, punching and kicking the shit out of the air around me, until the shaman came to help. She sucked the poison out of my heart, and spat it into the bucket.

I returned to the ashram for an all night ceremony in honor of Lord Shiva, and went straight to Durga’s shrine. Before I sat down to meditate, I removed the guru’s image from the wall. A couple hours later, the swami called me into his office. He told me this isn’t our house. I can’t, I interrupted. He quickly corrected himself and said, this isn’t your house, you can’t do what you want. I told him this is a community. He said, no it’s not. I understand that there is a hierarchy, I said. He said he needed to know that I wouldn’t vandalize. I told him there’s an ideological problem, it’s not vandalism. He said yes it is. I said sometimes disobedience is important. He repeated himself: I need to know you won’t vandalize. I said, I’ll tell you what I’ll do, and as I said the word Durga, the director suddenly popped his head in, didn’t look at me, and told the swami they needed to talk, after we were done. Then he looked at me and bowed his head. I bowed mine back and he left. I didn’t realize the director had gone to Durga right after me, and was trembling in fear to find another image down. I told the swami I still wanted to come, but I would have to take the guru’s image down if I went to pray with Durga. He told me I couldn’t go to Durga then. I said, okay, that’s sad, I feel a strong connection there. He said, it is sad, and he was furious. Then I told him I wouldn’t teach yoga with the images up, and that I would never say the guru’s name. He told me then I couldn’t come back. I got up, said it is what it is, and left. That night, to honor Shiva, I wore a tiger print suit to ceremony, and a blue scarf around my neck. Nilakantha, the blue-throated one, who drinks the poison of the world and transmutes it.

The next morning I asked the director if we could talk. I still believed. I spoke of reform, of the healing of rape survivors, of feeling so connected with this community. He told me I wasn’t part of the community, and that me and my kind should go heal somewhere else. He said reform was impossible; it would lead only to anarchy and chaos. I told him it was my dharma to take those images down. He was disgusted, and told me I was nothing but an iconoclast with dirty hands. Then he told me he didn’t care what happened after he died, if the images came down then, but that it was his dharma to honor and uphold his guru as long as he lived. He swore me to secrecy twice during our conversation. He told me his militant feminist college girlfriend had raped him too. I thanked him for the conversation and left.

* * *

I couldn’t sleep for months, I kept hearing their words, seeing our encounters unfold. I still wanted to return, thinking I needed to fulfill my vision, but the pandemic shut-down showed me my place. A wise woman told me that the visions do what they need to do to get us where we need to be. Their truth is in how reality unfolds. I had clung desperately to my vision of cosmic love, and it emboldened me. I believed a love so pure had to survive, that it would bring us together to eliminate corruption and spread light. It didn’t. But it showed me myself. When I was finally ready to feel the pain of that experience in my body, instead of watching it replay incessantly in my head, I had a dream. I was naked, trying to pray secretly with a group of Jewish men from behind a rock wall, and then the swami walked around the perimeter, right in front of me. He was bare chested, and on his left rib, he had a bright black tattoo of the Eye of Horus. I fell into that symbol like a well, and when I awoke, I did some research. Horus loses his eye to his uncle and sexual violator, Seth, who has murdered their father. Horus’s eye is magically restored, and comes to symbolize wholeness and healing. The symbol, however, is also known as Wadjet, who is the Solar Snake Goddess of Lower Egypt, a fearsome and fiery protector. I remembered that as young girl, I had made and worn a mask full of snakes, and stood in front my grade-school classroom as Wadjet, speaking words from the Book of the Dead:

Wadjet comes to anoint your head in flames. She rises up and shines without speech, rising upon your head during each and every hour of the day. Through her, the terror that you inspire in the spirits is increased. She will never leave you. She strikes into souls, and they are made perfect.May she, in her wisdom, continue to strike me and strike us all, for the sake of healing and wholeness.