Emily Balsamo

(Pere)(pere)(pere)stroika, or a Divorce Between the Signifier and the Signified

ISSUE 9 | RECONSTRUCTION | OCT 2011

Illustration by Tom Tian

Walking through the streets of Moscow for the first time, you can’t help but feel that you’re not supposed to be there—that you’ve broken into a house whose owners are out of town, but intend to return shortly. Once the novelty of Soviet ruins fades and you come to see the city as a home (of sorts), you still can’t help but feel that the place can never be yours. Even lifelong inhabitants and the governing class appear to take no real responsibility for the city; everyone seems to be squatting rather than owning. There is a palpable distance between the built environment of the city and its people. When one asks why the government doesn’t remove the behemoth Soviet monuments and distinctive Soviet architecture that punctuate the city, the most common answer is something along the lines of: “We didn’t put them there, why should we take them down?” The haggard бабушки (old women) who peddle nuts on the street feel themselves to be a part of a nation that no longer exists, while the New Russian consumers identify themselves with a nation that cannot take responsibility for its materiality, for its landscape. Nobody is really living in the present; some are living in the past and some are living in a false idea of the present, a present without a past.

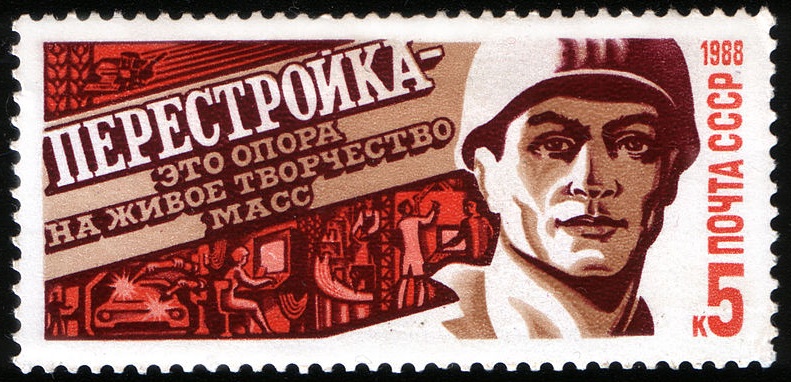

Perestroika, Russian for “reconstruction,” generally refers to the period towards the end of the Soviet Union during which Gorbachev sought to restructure the Soviet system, making it more conducive to international and domestic trade. Despite the fact that these programs stood in opposition to the prior economic policies and stated ideology of the Soviet Union, the styles of propaganda produced to promote Perestroika were similar to those used in the past. As a 1988 stamp, designed to evoke the style of 1920’s Soviet constructivist graphic artist Alexander Rodchenko, defines it, Перестройка: Это опора на живое творчество масс, that is, “Reconstruction: the backbone of the living creativity of the masses.” This slogan could just as well support one of Stalin’s 5-year plans, Lenin’s NEP or the 1917 revolution itself, while the graphic style of the illustration could easily blend into a collection of Leninist propaganda.

This reference to past ideology through graphic style, this repurposing of a visual form which had been used to support very different ideas for decades, provides continuity with the past, although the policy (segue into capitalism) and consequences (catalyzing the fall of the USSR) of perestroika stand in sharp opposition to the previous ideology of the Soviet Union. Here the old Soviet system lives on, if only aesthetically, in the graphic and rhetorical design. Glavlit, the Soviet entity that controlled the press, tried to maintain such consistency right to the bitter end, even in the face of its own new policies, which stood in profound contradiction with its previous commitment to Soviet communism.

Perestroika saw the final phase of Soviet propaganda, which had been produced in a constant stream ever since the Russian Revolution. This material stood not only for communism, but also for the specific Soviet system of the time. It drew its significance from the relevance of Soviet communism to the every day lives of the people. The stream was self-perpetuating; prior propaganda produced a generation of loyal devotees, laying the groundwork for later propaganda. The effect of propaganda was very real: it produced feelings of nationalism, pride, and security among many Soviet citizens. In the Soviet Union, the government was the source for people’s housing, food, employment and general well-being. Propaganda served to produce a sense of confidence in the government, which was necessary for the continuation of the system. One of the most effective features of Soviet propaganda was that it was instantly recognizable and comprehensible. One did not have to be literate to draw pride from an image of two confident-looking farmers with impeccable posture painted in bold colors. The union of art and architecture created an aesthetic continuity; everything was recognizably Soviet.

But why are these aesthetics so important? We have been conditioned to take the rhetorical and graphic style exemplified here as a cue to the social and political significance of the stamp. There is nothing inherent in the bold shadowing and steadfast expression of the figure that implies a particular political position; we know this style to be politically significant because we have been trained to understand it as such. As a result, it is impossible to employ this style without a nod to the period and politics with which it was originally associated. A particular history and culture have established this style as an indication of hard-line Soviet policy. While this stamp does not in fact stand for such policy, its use of these aesthetics establishes a false sense of continuity with the past. Yet the aesthetics and rhetoric that denote Soviet policy are arbitrary; they are simply components of recognizable signs.

Ferdinand de Saussure discusses this arbitrary association in his Course in General Linguistics. He distinguishes two aspects of the sign: the signifier, a sound or image which has been assigned a particular meaning, and the signified, the concept to which the signifier refers. Take, for example, a 200-ton statue of Karl Marx. Our perception of the statue in the form of a mental image is the signifier, while the concept that it stands for, proletarian revolution, is the signified. In this case, the concept, the signified, is unequivocally political, just as Rodchenko’s style of graphic design is irrevocably linked to the political motivations implied in it. A monument to Marx necessarily signifies much more than the representation of a specific person, because Marx himself is a sign. Considered as a sign, Marx’s signifier is our perception of him, and his signified is the individual, Karl Marx. The individual Marx’s signifier is an image of him, or his written name, while the signified is his ideology and its result, communism. Not theoretical communism, but the foundation of the livelihoods of 200 million people for 80 years: communism as an ideological opposition to the greedy capitalism of the West, as the pride of the fatherland and the belief that those who had perished in World War II had not died in vain.1 The signified entity was the relevance of communism to the lives of the people.

We approach concepts in the ways that we have been conditioned to approach them, depending on the ways in which we have been taught to understand signs. In order for a language, for example, to be functional, Saussure argues, there must be a social consensus on the signifier/signified relationship. We must agree that the written word ‘tree’ refers to our perception of a tree (a large carbon-based plant) in order for the word to be of any use. Lenin, in 1920, conceived a statue to be built of Karl Marx on Teatralnaya Square in Moscow because there was a social consensus as to the signified, Marx = communism. Moreover, the statue is laden with socially accepted signs in addition to the likeness of Marx, such as his erect posture, his confident expression and the phrase, “workers of the world, unite!” The style of rendering, too, is distinctive; it signifies a Soviet political message, much like Rodchenko’s style of graphic design.

Many of the signs that refer to Soviet structure and ideology had been deliberately created; the social consensus as to the signifier/ signified relationship had been forced. Constant deliberate exposure to recognizable aesthetics and styles of rhetoric systematically enforced by organizations such as Glavlit created a clear system of signs that were easily readable. Perestroika attempted to maintain this semiotic consistency while propagating counter-Soviet policy. The post-perestroika era yielded further “reconstruction” and an official distance from the propaganda of past. The constant stream of propaganda which had once created a consensus as to the meaning of signs suddenly ceased. The signifiers themselves, however, the ubiquitous images of signs past, manifest through statuary, architecture, art and literature, remain in place. The significance of these signs lay in the constant affirmation of the value and relevance of Soviet communism in the lives of the people. Once this affirmation ceased, moreover, once the value and relevance of Soviet communism was officially denounced, the significance was lost. What becomes of these signifiers once what they once signified has been removed? Once the relevance of communism had faded, what became of what stood for its importance?

In the physical sense, perestroika was not reconstruction at all, but re-labeling, a social reconditioning. The physical landscape of the old country, the infrastructure, statuary, architecture, decadence and organization remain, but the official attitudes toward them have changed. The statues of Marx are no longer officially meant to glorify his image, but are to officially signify nothing. The KGB is to be renamed the FSB, but is to be comprised of all of the same people and located in the same building in Lubyanka Square. The Kremlin is to maintain its name and function, but is to be the residence of the President and Prime Minister rather than of the General Secretary of the Communist Party, or of the Czar, as it once had been. The referents are the same; history existed, but the ways that it is socially appropriate to understand the signs have changed.

In Saussure’s system, a monument is both a signifier and a signified; it is both a referent in and of itself, and a signifier meant to belie something else conceptually. But what happens to the signifier once the signified, the relevance of the Soviet system, is taken away? That is, what becomes of the sign once the signified is nullified? As S.I. Hayakawa discussed in his 1949 piece on semiotics, Language in Thought and Action, “The first of the principles governing symbols is this: The symbol is not the thing symbolized; the word is not the thing; the map is not the territory it stands for.” If the word is not the thing, is the thing the thing? If a monument to Marx was originally meant signify the glory of his legacy and the relevancy of his work, what does it mean once his legacy has been defamed by the same authority that once erected the statue?

What has resulted is confusion and disconnect between the signifier and the signified, making the signs unreadable. Rather than subscribe to the new system of signs regarding the old regime, many people would rather not read a sign at all. I was once walking with a Muscovite friend, a New Russian student at the State Economic Institute, a classmate of President Medvedev’s son. I pointed to the aforementioned 200-ton statue of Marx, in Teatralnaya Square, facing the Bolshoi Theatre in the central part of Moscow. I asked of whom this monument was, unable to read the text from a distance. She replied, “Something communist, I don’t know, I don’t like communism.” Born in 1992, she never experienced communism herself, and despite being surrounded by physical remains of the system, she has opted out of an understanding of the past in order to look forward.

I am not asserting that all citizens of states of the former Soviet Union live in ignorance of their countries’ past, though my sense was that the overstimulation of political symbolism of the USSR has left a vocal portion of the population desensitized and apathetic to what the surrounds them once stood for. Signs have been reconstructed, that is, redefined until they have been rendered meaningless.

ПРОЛЕТАРИИ ВСЕХ СТРАН, СОЕДИНЯИТЕСЬ! Workers of all countries, unite!

1 The Soviet Union lost 27 million people in WWII, 14% of its population. This loss comprised 45% of the total deaths of the war.