Olivia Durif

That Open Road

ISSUE 60 | SEE AMERICA | JAN 2016

I spend Thanksgiving driving across the state of Arizona. Flagstaff, Winslow, Meteor Crater. Nothing is open except gas stations and one place serving a 24 hour Thanksgiving buffet. We buy black coffees and ask if we can get a slice of pumpkin pie without spending 25 bucks on bottomless gray turkey and mashed potatoes. The watery, comforting slice comes without a fork, in a styrofoam container. The state along highway 40 is a shade of pale, brownish pink that’s hideous in upholstery and paint but perfect against sagebrush, ruddy dust and ochre sandstone. The old, peeling signs from Route 66, still lined up along each side of the freeway are unsettling, to say the least. Do the locations they point to—teepee-shaped motels, fossil fields, reptile farms and huge, fading pastel-painted dinosaur statues—actually exist, or are they mirages, signs with no referents, pointing and inviting me towards the strange urges and disembodied visions that smolder and surface after driving 10 hours straight? That the entertainment offered on this highway is either about dinosaurs or Native Americans must be somebody’s sick joke.

Road trips are, at heart, inefficient. You have a destination and you take a long time to get there. In two months we’d become experts on stuff. Items we determined necessary to survival or comfort, which are easy to confuse. We referred to our stuff as gear when it was useful and bullshit when it wasn’t. Clothing, food, tents. Sometimes our stuff was a huge problem: who the fuck decided to bring this bottle of balsamic vinegar? Baby, I can’t drive another fucking mile with those nasty pants in the cab. The 4th floor of a parking lot in Santa Monica was an arena for the biggest meltdown on our 5000 mile trip. About to leave the truck behind for a few days while we crashed at a friend’s house, I wanted to bring everything I owned with me and also throw everything I owned away. I stuff a backpack with my towel, bikini, jeans and some cigarettes. Shannon brings a dress, half a loaf of bread and a jar full of butter. We get our shit together and have a great time in LA. I think, between Oregon and New York, the only thing I lost was my copy of The Grapes of Wrath, in a Best Western in Braselton, Georgia.

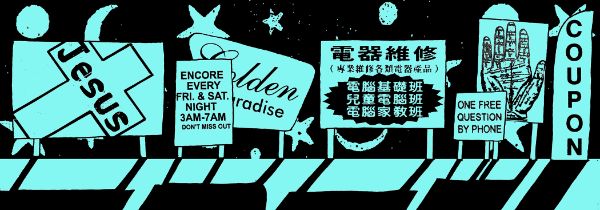

Illustration by Katie Marshall.

In American road trip stories, travelers—buddies or lovers—move across the “empty space” of the country and create a community of two, hoping to gain new senses of themselves as individuals. The travelers are searching for something. Often they don’t know what it is. The travelers consider themselves outlaws, having abandoned the rules and regulations of settled society, but they find themselves outlaws in ways they didn’t expect. They’re only pretending that the land they’re traveling through is uninhabited. Finally, they’re outlaws because they’re betrayed by the land, which turns out to be peopled already. It turns out you can’t create a population of two: the world outside of your car is full of other people, and the world. You can never get far enough away. Freedom from place and routine turns out to be another kind of prison.

One particularly dark and alcoholic winter, West and I spent our nights at a bar called the Sundown. The bar has this old pockmarked, red felt pool table that we blamed for our shitty games. The juke box never played loud enough. She was twice my age and I loved that her last name was a coordinate. She drove a black motorcycle and liked to litter, which I also liked. Once the bartender cut us off, which I didn’t realize could happen in real life; we decided it was a hate crime and it probably was. My drink was a whiskey with soda, bitters and at least two limes—only a few rocks and just a splash of soda—please , thanks. It’s an excellent drink and a pain in the ass to order with a swagger. But a whiskey soda really isn’t the same. West started going up to the bartender and just ordering an Olivia Durif. What? You don’t know how to make it? Jesus, well, let me tell you how it’s done. Much cooler and less polite than I’d ever been able to order it myself. On one of these nights we set out to construct a Road Trip to Nowhere. We sat down and wrote out arbitrary directions on little slips of paper: go 50 miles north, at the first shell station, buy a pack of Cheetos, dump out the Cheetos and multiply the number by 2. Go that many miles east. It was like that. We must have written out 50 directions. We’d give ourselves three days on the road and see where we ended up, our agency thrown out the window, our route determined by our ridiculous directions, and fate. The next morning we still thought it was a good idea. We set out.

*

In the first shot of the Ride music video, Lana Del Rey is part child, part pin up, playing on a tire swing in the middle of the desert, suspended from the heavens. The video has a 4-minute long, spoken introduction that begins with a dramatic flair that’s both porny and weirdly like a 19th Century novel: I was in the winter of my life / and the men I met along the road were my only summer. Throughout the video, Del Rey is shown either enjoying moments of reckless abandon—shooting guns, playing arcade games, driving fast on the back of a burly man’s motorcycle—or looking like a child prostitute. While many of Del Rey’s songs explicitly reference Lolita, the Ride video is replete with imagery of the sexualized girl-child: getting her hair brushed out by a big, old biker on a hotel bed, sitting on a different old guy’s lap in a small white dress. In one scene, Del Rey, wearing red high-topped sneakers and denim shorts, trips over her feet, looking both like a drunk and a kid playing hop scotch.

Illustration by Katie Marshall.

I’ve been out on that open road / You can be my full time daddy, white and gold / singing blues has been getting old, you can be my full time baby, hot or cold. What is a “full-time daddy”? Is the promise “you can be” in keeping with the video’s slutty overtones? Is LDR singing out to all the could-be daddies at large on the road of life? Anyone can be her daddy, for a minute. Or does Del Rey want a more accountable relationship? She’s tired of not having a home, of spending her life with only part-time daddies, ready for something more reliable. At the end of her intro, Del Rey invokes her mother for the only time in the song: my mother told me I had a chameleon soul. Maybe Del Rey is ready for a more a dynamic relationship, but she’s essentially unsuited for it—“born to be the other woman”—whether she likes it or not. Maybe the switch in this verse, from “full-time daddy” to “full-time baby” is not an example of the “inner indecisiveness” that her mother blames her for. Maybe Del Rey wants a daddy who can also be a baby—a lover with whom the balance of power is mutable, rather than confined by a stifling teleology. But if Del Rey is truly tired of the road and looking for a new kind of intimacy, the video keeps returning to stylized, romanticized images of life with her gang of road daddies: hands up, face in the wind. Being on the road as a child, feeling free: that backseat feeling. Bliss of riding bitch.

*

West and I were sure that our relationship was doomed, that age had something to do with it and that the road would be the answer. The road compresses time, so does age difference. Both parties feel like they’re cheating time. The relationship is, like the road, a sanctuary. The road is a queer space, outside normative concepts of orientation. A terrarium where life gets enacted on a small scale—a container in which you get to set your own time and be delighted by spaces you didn’t expect to inhabit. Stories from her past make me restless for my future, kind of sad and jealous. Closeness to the gays that came before me is a thrilling history lesson and a swaddling comfort—shhh, baby—a glimpse into the dyke I’m becoming.

Illustration by Katie Marshall.

It’s good, in a relationship, to feel like a baby sometimes and a daddy other times. Sometimes it’s good to feel like both at the same time. In Lolita, Humbert says his passion for nymphets comes, not from their sexiness, but from “the security of a situation where infinite perfections fill the gap between the little given and the great promised.” This is Humbert’s crime: a temporal perversion, to make a road trip of a human. To fill up the anxious space of unforeseeable growth with secure—because constructed—fantasies of pristine eternity. To capture time, and ride it into the sunset. Because otherwise you’re left with what lies between the given journey and the promised destination: a truck full of stuff, a sweet girl, other people and (ah!) yourself.