Caroline Lemak Brickman

The Covers Record

ISSUE 43 | BAR | AUG 2014

He says, right off we don’tServe fine wine in half-pints, buddy.…Little things do wear out your welcome, that I know.One is clothes, the perfection of the body.

[…]

Just, for instance, words from a gentleman behindThe bar – a sort of prisoner: we

Don’t serve fine wine in half-pints, buddy.

…How could he know that’s my name?

[…]

We Don’t Serve Fine Wine In Half-Pints, BuddyIs the sound of God.

Robert Ashley, Perfect Lives: An Opera

Chapter IV: “The Bar (Differences)”

I.

The first song on Cat Power’s The Covers Record is “(Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” She doesn’t sing the chorus. The result is wild, it’s like something out of Hesiod: there are certain songs the cover artist steals but not this one, she couldn’t take it from Jagger, couldn’t make it her song, and when appropriation failed she let it take her instead. Instead of signing her name to the song she tries to erase his sign and put her name to the erasure. Working in miniscules. Naturally this devastating move only shines more light on him not her but you squint and realize that light is her.

Now her version of “Moonshiner.” It’s on the album Moon Pix. The song is about a bar. The bar is a communal space of solitude. It has room to reckon with the self and the public at once. Power follows Dylan’s version closely except for a classic Power cover trick: Dylan’s salty-sorry-sweet “God bless them pretty women / I wish they was mine” becomes a cry of misery – “God bless them – handsome men – I wish they were miiiine.” (The contempt and the certainty she can’t have them, you almost wonder, is she quoting Cohen?) I say classic Power cover trick because of these lines from her “Satisfaction”:

And I’m doin’ this and I’m signin’ that

And I’m tryin’ to meet some boy

As though boys could be met. As though handsome men could be blessed then had.

The “Moonshiner” cover features two original lines. They come late in the song, just after the handsome men, and they’re startling.

You’re already in hell, you’re already in hell

I wish we could go to hell

The stakes of the song skyrocket. The bar is a road paved with intentions and “already” a dead end.

I have wondered: do these lines startle the listener unfamiliar with earlier versions of the song? On the one hand, the answer is yes: the song gains in pitch what it loses in sense; a “you” appears ex machina. Unlikely words are emphasized: “in,” “go.” The song ends very quickly soon after. Possibility and impossibility are introduced in rapid succession, spikes in a landscape which had been flat like a fable.

The question is misguided. One may as well ask: do these lines startle the listener unfamiliar with drinking establishments, with love disparate and unrequited, do these lines startle the listener unfamiliar with hell.

The questions this volta wants are more like: has the cover failed? Has Power failed the song? The space of the evening collapses: has the bar failed? Has the bar failed her? (Hadn’t the bar failed the first moonshiner? No: pretty women may be desired then had.) But the bar holds promise: I wish we could go to hell: a threshold has been crossed, the space of the evening coheres anew.

II.

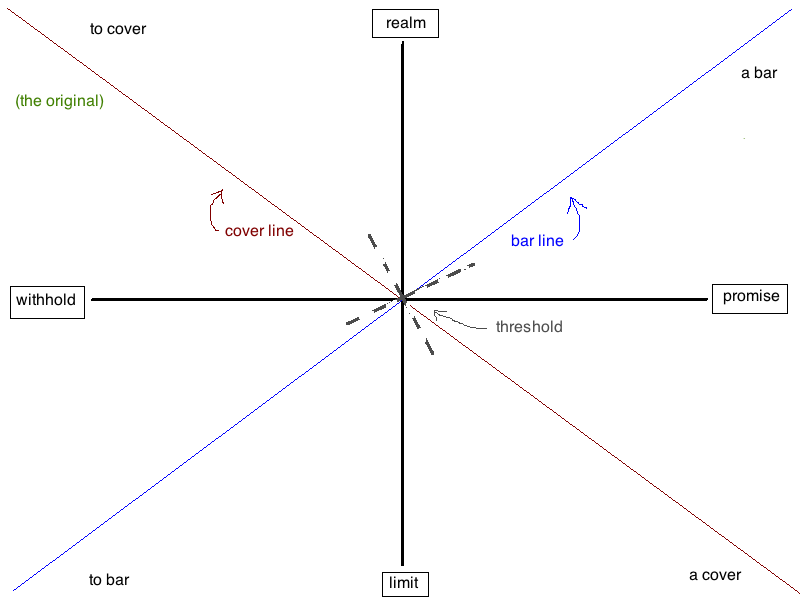

Consider this diagram. It intends to chart how the word “cover” may relate to the word “bar.”

The relation involves a horizontal axis: where the verb “to promise” opposes the verb “to withhold.” They belong on the same axis because neither grants: one says it will, one says it won’t. The vertical axis asks a dimensional question: it lets a body of space (“realm”) oppose a line or boundary (“limit”).

The central point of intersection is the “threshold.” The bar line runs from the lower left quadrant (where to limit is to withhold) to the upper right (where a realm offers promise). The lower left quadrant is governed by the verb “to bar,” the upper right by the noun. The cover line runs from the upper left quadrant (where a body of space withholds) to the lower right (where the limits of a form may promise). The upper left quadrant is occupied by the verb “to cover,” the lower right by the noun. The threshold is the center both of the vertical limit-realm axis and the horizontal withhold-promise axis.

The tendency of the diagram is to move from left to right along the diagonals. The cover line crosses the bar line at the threshold. The threshold is the entrance to the bar. It is where actions (left side of the diagram) and their products (right) are least differentiated. For instance: the cover artist, stuck upper left with the original (ugh, another man’s song), must act to cross the threshold and emerges bottom right with a cover. Thus the limits of the form (ooh, another man’s song) reveal themselves to be full of promise.

III.

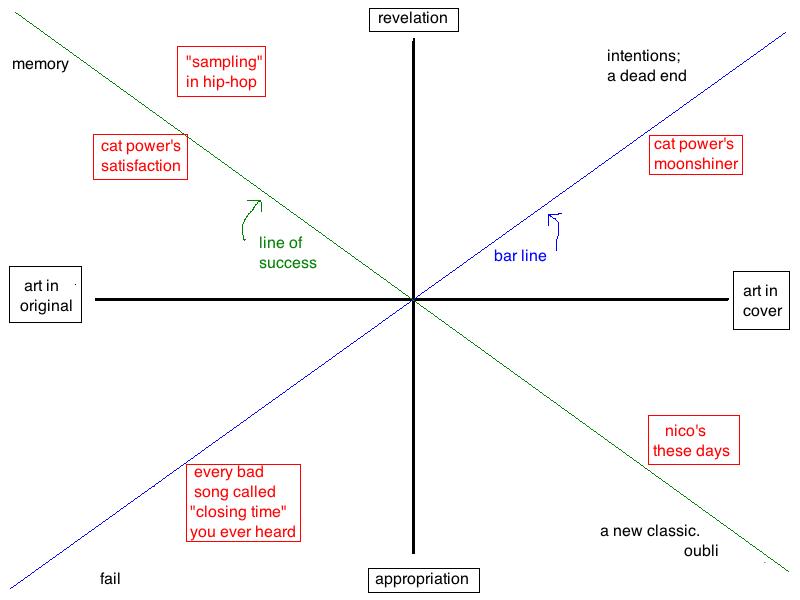

The cover is a genre paved with intentions and already a dead end. Why do you go to a bar and then why do you stay. And is there more “going” that happens in that “staying,” and even if there wasn’t last time won’t there be tonight. The word cover is so beautiful because of course the cover qua cover version can neither conceal nor inhere. It can only appropriate (at which point it is no longer a cover proper), or else it can reveal.

The appropriative cover is a phenomenon that bores me because the successes are miracles and the failures have no art. The revelatory cover has art no matter what – in itself, sometimes; in the original, sometimes; in their relation, best of all.

The word bar is so beautiful because the limit beyond which becomes the realm within which. Becomes or points to? I think it becomes, and that’s why you go, and then you see it’s not a realm it’s a limit; that’s what happens the longer you stay. Realm limit realm limit. You hope revelation will happen. I wish we could go, etc., to hell.

IV.

There are interesting covers that don’t belong to the bar. Perhaps they belong to the bedroom: most examples that come to mind turn on sex not solitude. The Cowboy Junkies’ “Sweet Jane,” k. d. lang’s “Hallelujah,” Lyle Lovett’s “Stand By Your Man.” Cat Power’s “Satisfaction” hangs out on this list too depending on the time of day. Have you ever heard Nina Simone’s “Just Like A Woman”?

By now it shouldn’t come as a surprise when I say that these covers are all interrogating their status as covers. But they do it in different ways. Simply put, “bedcovers” ask, “am I the same or different?” (Which is why covers queer so well.) And “bar covers” ask, “how far can I take this?” Bedcovers reckon with themselves in relation to another; bar covers reckon with themselves in relation to the conditions of reality.

To follow the terminology developed in diagram 2, we might say that Cat Power’s “Satisfaction” treats itself as though it has slid down the diagonal line of success into the “new classic” quadrant. We have seen how Power-the-cover-artist treats crucial moments in this song – moments most to do with signature – she erases them. Jagger’s chorus long gone, she grants a new set of lines this status. A set of lines she’d already claimed. The song ends:

And I’m doin’ this and I’m signin’ that

And I’m tryin’

And I’m tryin’.

The Hypocrite Reader is free, but we publish some of the most fascinating writing on the internet. Our editors are volunteers and, until recently, so were our writers. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, we decided we needed to find a way to pay contributors for their work.

Help us pay writers (and our server bills) so we can keep this stuff coming. At that link, you can become a recurring backer on Patreon, where we offer thrilling rewards to our supporters. If you can't swing a monthly donation, you can also make a 1-time donation through our Ko-fi; even a few dollars helps!

The Hypocrite Reader operates without any kind of institutional support, and for the foreseeable future we plan to keep it that way. Your contributions are the only way we are able to keep doing what we do!

And if you'd like to read more of our useful, unexpected content, you can join our mailing list so that you'll hear from us when we publish.