Sandow Sinai

Material Mindfulness

ISSUE 95 | SYMPTOMS | JUL 2020

Hermeneusis

A narration:

I am sitting in front of a drum set in a poorly-lit practice room, listening to music and attempting to play along. I reach a passage in the music that requires me to play a relatively quick succession of notes with my foot on the bass drum. It’s not difficult for me to play a few consecutive notes at this speed, but sustaining it for a longer period of time is difficult, perhaps impossible, at my current level of muscular endurance. I am conscious of this, and conscious of the fact that a more skilled drummer than myself would have no trouble sustaining this motion. But I am practicing, not performing; as much as my goal is to execute the passage, I’m also trying to expand the boundaries of possibility, to chip away at the real inadequacy underlying my possible failure.

The more tired my leg becomes the more present my leg is in my consciousness. I feel a sudden stimulus just above my knee. It’s not a tangible sensation, but rather an abstract psychosomatic desire–what neuroscientists call a “premonitory urge.” As I become more aware of the affected area, in proportion to how hard my muscles are working, the premonitory urge grows too, until suddenly the muscles surrounding my knee briefly contract–the “tic” of my chronic tic disorder.

The fact of this tic’s occurrence is an implicit source of knowledge. It is, after all, a symptom, which, translated from its Greek root, is a happening, an occurrence, a phenomenon. Medical theory distinguishes between a symptom–that is, the phenomenon itself–and a sign–that phenomenon acting as a signifier of something. The sign carries knowledge; the symptom does not. I am aware of this distinction, but physicians making a diagnosis do so from the outside; in my internal experience, there is no symptom that is not a sign. The medical professional’s concerns are physiological; the knowledge they derive from the tic is that of a diagnosis. Internal experience, however, doesn’t have the luxury of being so tidy. I could say, after all, that the tic signifies to me that I have a tic disorder, but while that knowledge could be useful insofar as it connects me to discourses from research, media, and others who have similar disorders, it is also, in a substantive sense, meaningless. I already know that I have this diagnosis, and I have known since I was seven; whatever specific message an individual tic has for me, it’s not medical. So what knowledge can I derive from my tic? What precisely does it signify?

I am sitting in front of a drum set in a poorly-lit practice room, listening to music and attempting to play along. A tic in my knee just threw off my groove. I pause the recording and take a deep breath. As I inhale, I focus on the affected body part. Other premonitory urges may develop, and I may tic again, several times. I may tic in other body parts, particularly ones related to the motions I was carrying out; my toes and gluteals, my other knee, my elbows and shoulders, each offering their own chains of signification. I listen to my body’s signals actively rather than passively, seeking to derive as much meaning as I can from the things my body does that are outside my control.

I reconstruct the narrative as I presented it above, or, to be more precise, I reverse engineer it. The tic first signifies to me that I was aware of my body. This seems oxymoronic (how can you be aware and not know it?), and it is, so by implication the tic signifies to me that my bodily awareness had some quality of anxiety. This is to say, before the tic, I was trying to do something that I was not sure if I would be able to do. At the core of this internal mechanism is my own hypothetical inability to execute the passage. This possibility of failure produces a desire for more advanced technical skill, as desire is precisely the gap between what I demand and what I have. My musical failure , though, itself “fails” in a sense, because it is a possibility, rather than a certainty, of failure. My anxiety is the gap between what I know I can do and what I’m not sure I can do, given form. The longer I sustain the task that I am only maybe able to accomplish, the more the possibility of either success or failure becomes tangible, and the more the anxiety intensifies.

The knowledge and experience I have accumulated of my disorder allow me to read the tic as a signifier of anxiety. The thought process I just narrated is, essentially, a reinvention of the psychoanalytic thought of Jacques Lacan: in his terminology, my failing to execute a musical task would indicate a “lack.” For Lacan, lack–that is, the knowledge that I might fail–is always incomplete, because failure is not a certainty. Lack itself, therefore, is lacking; the “lack of a lack” is constitutive of anxiety, and a consequence of the desire to “repair” the lack, to overcome imperfection. This anxiety always necessarily signifies desire, and the desire in turn signifies a lack, and all three signify a complex of related lacks, desires, anxieties, subjectivities.

My tics, therefore, are rooted in how I perceive myself as deficient relative to an Other– in this case, drummers who are more technically skilled than me. This comparison, in turn, points to a broad array of associations: from my desire to honor and emulate past great drummers (a desire intrinsically tied to my racial subjectivity due to the historical position of the drum set as a Black medium); to my responsibility as a time-keeper for those I might perform music alongside; to my experience playing other instruments professionally and my desire to hold myself to a high standard even on a less familiar instrument; to my position as a working musician needing to meet my basic needs of social reproduction and as woman anxious about proving myself to my male colleagues. The tic brings me outside myself–far from being a mere signifier of diagnosis, it explodes into a vast network of phenomena that, rather than being components of my individual psyche, span almost every aspect of my social being. Further, as much as tics are a private, individual experience that resocializes me to the world, they also point towards something approaching agency; that is, towards a way to mobilize this knowledge towards decision-making. Narration:

I am sitting in front of a drum set in a poorly-lit practice room, listening to music and attempting to play along. I reach a passage that requires me to play a relatively quick succession of notes with my foot on the bass drum, which is difficult to sustain. As my leg tires, its physical presence becomes more prominent in my consciousness. I feel a sudden sensation just above my knee–a premonitory urge. I know I am going to tic soon. I’m immediately self-aware: I continue playing, but my limbs are acting on muscle memory. Instead, my focus is on actively thinking about my body, about the tic that is about to happen. It is a simultaneous moment of observation and decision-making. At this moment, I get to decide what the tic means because I get to decide what I am going to do about it. I have the option to ignore it, to allow it to happen unexamined, and try to continue playing; the option to suppress it outright (though this rarely works for long); the option to transfer it to another body part where it will be less disruptive by focusing on the part I’m playing with that body part; the option to follow the advice I would give my students and focus on breath, relaxation, and the dissipation of tension; the option to concentrate on the music in my earphones and cathartically disappear into the sound. If the moment following the tic is the moment of reflection, where experience transforms into knowledge, the premonitory urge is the moment of decision, where knowledge is transformed into power.

Mindfulness and Collective Action

Joint energy disposal in parts of singular feedings. A recharge; group chain reaction. Acceleration result succession of multiple time compression areas. Sliding elision/beat here is physical commitment to earth force. Rude insistence of tough meeting at vertical centers. Time strata thru panels joined sequence a continuum (movements) across nerve centers. Total immersion.

—Cecil Taylor

My ability to engage with my tics meaningfully rather than treat them as an annoyance to be suppressed is a skill I developed under the guidance of a wonderful therapist I saw from age 17 to age 22. My therapist would describe her general approach as “eclectic,” but, among her influences, it is hard to ignore a psychotherapeutic tradition broadly called “mindfulness.” Mindfulness is a meditative practice, loosely derived from Buddhist principles, that has seen widespread popularity in Western contexts since the 1970’s. Jon Kabat-Zinn, who developed the clinically popular Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program and who is widely credited with popularizing mindfulness in the West, describes it thus:

Simply put, mindfulness is moment-to-moment non-judgmental awareness. It is cultivated by purposefully paying attention to things we ordinarily never give a moment’s thought to. It is a systematic approach to developing new kinds of agency, control, and wisdom in our lives, based on our inner capacity for paying attention and on the awareness, insight, and compassion that naturally arise from paying attention in specific ways.

In his book McMindfulness, Ronald Purser counters this succinctly: “Anything that offers success in our unjust society without trying to change it is not revolutionary — it just helps people cope.” This is the crux of the anti-capitalist critique of mindfulness: that it is an individualist project of managing the stress caused by the material conditions of life in global capitalism without addressing those conditions. This argument is echoed by mindfulness’s other main group of critics: Buddhists disheartened to see the modern mindfulness industry sell, in the name of Buddhism, a meditative program stripped of the moral and ethical focuses that are critical to Buddhist practice. To be clear: I buy these critiques wholesale. I don’t believe I am entirely equipped to address the latter because of my own lack of knowledge about specific Buddhist traditions, but I will say that I hope to offer a mindfulness that, in opposition to the mainstream practice, starts from a carefully considered socialist ethic. As for the critique of mindfulness as individualist, the mindfulness I describe is not solely about techniques of individual self-improvement, but rather about a (proletarian) collective being communally mindful in service of the holistic wellness of the whole collective–which, as the Marxist tradition informs us, is synonymous with a revolutionary transformation of all social relations. If mindfulness is about body-knowledge and body-power, then collective mindfulness requires a conception of a collective body. Narration:

It is approximately 10:00 PM on June 2nd, 2020. We are in the midst of the George Floyd Uprisings. Following bourgeois panic about property destruction and expropriation, the mayor has instituted a curfew making it illegal for people who are not essential workers to be out past 8:00 PM. Tonight is the second night of the curfew, and some 2,000 of us have crossed the Manhattan Bridge from Brooklyn on foot. The NYPD have set up a barricade on the Manhattan side of the bridge and intend to prevent protesters from leaving on that side. I’m smoking a cigarette and nervously fiddling with my oven mitt, in case I need to throw back a tear gas canister. We are at a standoff.

If in my personal narrative the large-scale goal towards which I was working was to be a technically proficient drummer, here our goal is abolitionist: to live in a world without police, without prisons, without violence against Black people. If in my example, my practice (both as physical motor development and as building headroom for future expansion) was to play along to a recording, here the practice is proving our ability to act as an independent body capable of asserting our agency against police authority; that is, to prove our real ability to win this tactical battle and our symbolic ability to signify that we will win more.

Examining my own description of the goals and stakes of this moment, I cringe at myself a little–it reads as an optimistic projection of what I wanted this crowd to believe. But in a way, that cringe is the point: what I’m trying to do here is get you to feel me, to feel my unaccountable instinct that my read on this crowd was not projection, but recognition. That is, I didn’t just see my own abolitionist principles reflected in them, but I could observe them seeing their principles in me. There was a connection on the bridge; to keep each other safe, we had to feel each other. Mutual trust, borne of situational necessity, nourished this recognition, as it expanded outward into a collective consciousness–we all know what we all know. And we functioned as a collective body in this moment because we had an unspoken shared understanding to remain as one body; while we were not a hivemind, we were committed to following the democratic law of not splitting the group, even if it meant doing something that we, personally or as tendencies within the whole, disagreed with–we all do what we all do.

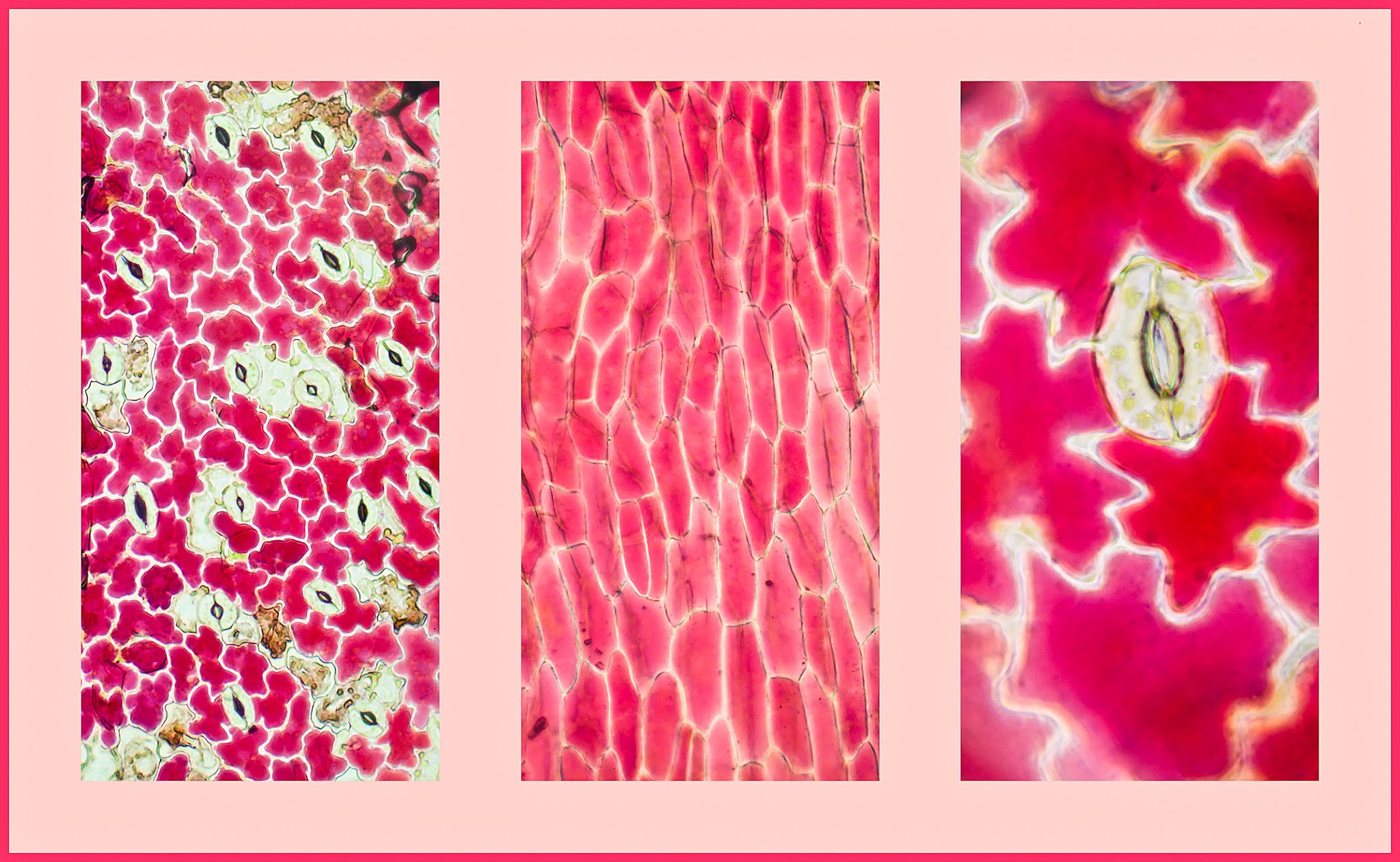

It is easy to overlook the significance of trust when analyzing a private, individual experience (such as in a practice room); it becomes much more necessary when we need to understand how mindfulness operates over a collective body. When I practice mindfulness in the petri dish of the practice room, the obvious question of trust is the question of whether I trust my limbs to obey me, to do what I want them to do, to play what I want them to play. But this version of trust is about subjugating the body to the will and trusting that it will dutifully obey; it is therefore entirely grounded within the logic of mind-body dualism. Mindfulness is about learning to trust my body, but this is necessarily a substantively different trust–that vulgarized trust, besides being philosophically suspect, is foreclosed to me because my body regularly acts against my will.

Mainstream metaconsciousness orients around two poles: the abject subjugation of the body, as in the case of the athlete forcing their body through discomfort so as to establish sovereign dominion over it, and the therapeutic recuperation of the body, where one fetishes psychosomatic “wellness,” as in the mindfulness industry. Both of these inescapably operate within the logic of mind-body dualism precisely because they both seek to individually resolve the contradiction between mind and body, to smooth over their contention and make them agree. But there is a reason the mind and body quarrel: the contradictions between mind and body are endemic to the division of labor, to the value-form, to the mode of production and the mechanics of social reproduction–think about the social meaning of my tics as a learning drummer, as a Black woman, as a working musician–so resolving them, short of the total transformation of society, is impossible. Mindfulness as I use it is not about overcoming the contradictions between mind and body; it’s about observing those contradictions. When that observation becomes a familiar habit, it transforms into recognition, which becomes trust. This trust is a working relationship, a contract of mutual aid, constituted by the commitment between mind and body to keep each other safe, and the mutual leap of faith to interpret any signals sent between body and mind as meaningful.

The political uses of this framework are obvious. The divide between mind and body writ large appears as the divide between the organized left and the proletariat. For decades, organizations from anarchist collectives to Marcyite microsects to the Democratic party have looked to control, speak for, or fetishize the working class. Even as proletarian mass movements appear (for instance, the George Floyd Uprisings), even the most well-intentioned of these organizations can never quite get in sync with mass movements. In response to this, materialist mindfulness can be an organizational ethic. But in the moment I’m narrating, organizations don’t exist; while there is leadership present, it is organized only on the basis of megaphone democracy. So here mindfulness is not just an individual therapy or a broad theoretical ideal, but a tool to analyze collective decisions and a preliminary method for individuals or organizations who want to lead mass action from within, rather than from without.

On the bridge, we're feeling anxious. This feeling is increasingly overpowering; the police are very deliberately escalating it. They have a helicopter flying overhead, which periodically flies low, intimidating us with wind and noise and harsh light. In addition to the ever-reinforced barricade in front of us, a squad of riot police is positioned to our side about six feet above us, ducking under a ledge, in an excellent position to ambush. Two vehicles follow behind us across the bridge to create the illusion of a proper kettle. We are uncertain of our safety and we are uncertain of our ability to maintain our safety. That is to say, the waveform of potential danger outside our control has yet to collapse.

We’ve been standing here for–15 minutes? An hour? I look at the ledge to our side, at the police stationed there to intimidate us, and I see them on their phones, taking pictures of protestor’s faces. I feel a jolt of anger. When I inhale, my abdominal muscles move before my throat allows air in; my breath is truncated by tension in my jaw and upper back, a drive to be belligerent, irreverent, ratchet. In most of daily life I am forced to imagine the police as Gods, as an abstract Other that I cannot engage with, much less overcome. Here I can imagine them as a concrete enemy against which I can assert myself. I want us to push past them, force our way off the bridge, not just for the catharsis of retaliatory violence, but to prove their obsolescence, to castrate them, humanize them, prove that we (this group, but also the abstraction of the people, the embodied revolution, etc.) are more powerful than them and don’t need them to protect us. I am not alone in this. I listen to the chants of the protestors around me–“NYPD suck my dick!” “Let us through!” “Fuck your curfew!”–and start my own: “Move bitch! Get out the way!” It catches on for a few moments–someone once told me that the fastest way to evaluate the ideological leanings of a protest is to start chants and see what sticks–and one tweeter would later use it as evidence that “the vibe here is overall very fun despite the impending doom”.

And there is a sense of impending doom. I feel this tension differently in my body, as a pressure behind my eyes (that, in a more vulnerable setting, might become weeping), as a proverbial sinking feeling in my gut. I breathe this emotion differently, too; here, when I exhale, my abdomen gives up holding air a moment and deflates before I can convince my throat to let air out. Periodically, someone in the back of the crowd shouts that we should turn back across the bridge. A few people do; not enough to seriously divide the group, but enough to make those that remain aware that turning back is an option. I feel, initially, a negative reflex against what feels like a concession of defeat, a failure, an admission that the police are untouchable. I catch that reflex before it becomes reaction, and allow myself to take the idea of retreat completely seriously. Underlying it is, perhaps, hopelessness, but also anxiety and resignation–the fear that the longer we stay in this situation, the more dangerous it becomes, and the desire for a safe, predictable outcome. In the rhetoric I hear from those elements of the group, I can identify points on which I disagree: some imply that the real symbolic victory would be to have defied the police and safely escaped, which both takes for granted that the exact same kettle would not await us on the Brooklyn side of the bridge, and ignores the sense of futility that attends letting the police say “we have the power to hurt you but we have chosen to let you go, provided you go straight home and don’t start any more trouble.” Despite this, the social contract of the collective body stands–I trust that those calling for retreat are not “outside pacifiers,” because I recognize the feeling of wanting retreat as my own. I’m tired, hungry, my shoulders hurt from carrying a bag full of protest supplies, my head hurts from nicotine sickness, my feet are blistered, and I desperately want to return to the safety of my home, my partner, my cat, my bong. I can understand their faulty ideas as products of desperation and anxiety, without being mistrustful.

Every so often, an older man yells that we should get on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram: use our platforms, and make sure the whole world knows the situation we are in. This represents a third “faction” in this crowd–those who want to win this battle by attrition. This plan is to wait peacefully on the bridge until one of three outcomes passes: the NYPD have no choice but to force us off, delegitimizing their mandate to “protect and serve”; the curfew ends at 5 AM, and we have proven our strength of will; or actors outside our kettle pressure the NYPD into letting us pass. I attempt to feel out what this means in my body, and realize that my body is left out of the equation entirely. Reaching this position requires not thinking about my breath or my body at all. This makes sense–we are not supplied to camp out, and the practical reality of potentially being here for another six hours is necessarily one of dissociation, ignoring the body’s needs, subjugating it to the will of the mind.

Mindfulness has let me observe the emotional reality of the situation, of the moment before the symptom, because I could recognize it in my own body. This can become collective knowledge if my comrades can do it too. If we want to change society through mass action, then, we ought to encourage this in each other and in our shared spaces; that is to say, it’s imperative that we build trust based in mutual aid and mutual recognition.

But collective knowledge is not the end goal in itself, as Marx’s cliche reminds us: “the point is to change it.” I took seriously the emotional core of the three strategic ideas that emerged on the bridge, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t have one that I believed was the right move. The premonitory urge inevitably collapses into a tic–the success of working class development, at any scale or level of organization, is about making sure that the tic is the right one. And critically, what “the right tic” is changes over time as our circumstances change and our enemies move against us. On the first hour of being on the bridge, we can be confrontational and push back the police. By hour three, we’ve exhausted our energy. When I check the police scanners, I see that protests elsewhere in the city have died down. We now have their undivided attention, and they have doubled their numbers. Ultimately, we retreated safely, which is cause to celebrate, but it is not the victory it could have been if we had acted more decisively earlier into the confrontation. If being mindful attunes us to a decentralized collective knowledge, we can harness it to not only make decisions in difficult situations, but to make those decisions more quickly.

The New Left was built around organizations; groups that derived their power from a tight central cadre, even as they related to mass movements. This was, in many cases, a strength, because of the efficiency and militancy with which groups like the Black Panther Party were able to operate, but it also became an Achilles heel; with the sophistication of espionage during the Cold War, programs like COINTELPRO were able to break the implicit trust underlying the organizational charter of party formations. In recent years, however, we have borne witness to the so-called “New New Left”–the decentralized militancy of Occupy, the Hong Kong protests, and the George Floyd Uprisings. The difficulty with this mode of action, however, is that it makes it difficult to make organizational, strategic, and tactical decisions quickly and efficiently. First, because it impedes the creation of “collective bodies” as unified formations that share basic commitments to stay united; and second, because even in a collective body the fear of that body’s collapse always looms, and its internal contradictions always threaten to reproduce its constituent’s traumas and foreclose the possibility of trust.

That the George Floyd Uprisings have birthed collective bodies of unprecedented scale is no small fact. The ability of these bodies to effect change is directly proportional to their ability to make decisions quickly without any element undermining the contract of trust that underpins the body’s formation. Materialist, collective mindfulness, then, is not merely a signifier of enlightenment. It is a practicable skill, like playing the drums, and our expertise in that skill scales up as we do: our project is to become its experts. We know that we can overcome the police’s advantage in resources by our sheer numbers. Now we have to overcome their advantage in organization–by loving each other mindfully, by connecting with each other through unity-in-division and solidarity-in-struggle, by recognizing ourselves in each other.

“We must love each other and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains.” –Assata Shakur

Sandow Sinai discussed this article in a panel discussion hosted by Hypocrite Reader entitled Doing Politics in/with Collective Bodies. You can view the discussion here.

Thanks to Bridget Daria O’Neill, Anja Weiser Flower, Michelle O’Brien, and Kate Doyle Griffiths for insights and reflections without which this piece would have been impossible; to Roxxy Putnam and Frankie Landau for being with me on the Manhattan Bridge that night, and the countless comrades whose names I don’t know; to my former therapist Pam McDonald, for equipping me to approach myself and others insightfully; to Erica Eisen and the rest of the Hypocrite Reader editorial board, for giving this piece a home and for being endlessly patient with me in the messy realities of the writing process; to Kit Eginton for being the best of all possible editors, for always pushing me to think and write as lucidly as I possibly can, for digging me out of intellectual and emotional traps, for being, at every stage, the first to realize when I sell my good ideas short, and for always being an unbelievably bright, supportive, honest, inspiring comrade. Above all, thanks to my partner Adrian Silva, because material determines consciousness, and any intellectual work I may do is only made possible because no matter how deep into the weeds I may be, however much I might neglect my needs, you always take care of me, and when you can’t, you remind me that it is my duty to take care of myself; it is my most profound wish to extend you the same courtesy.