James Meador

In Imitation of the Chinese

ISSUE 74 | CORRESPONDENCES | APR 2017

Valery Pereleshin's (1913-1992) remarkable life carried him from Russia to China and finally Brazil. He was at various times a Russian Orthodox monk and mystic, a translator for the Soviet wire service, and erstwhile erastes to a series of younger men who served him in turn as fonts of poetic inspiration. The poem reproduced and translated here was written in Rio de Janeiro in 1972, but apparently never intended for a wider audience. It was only published posthumously in 1994 by Olga Bakich, his biographer and scholar of the Harbin Emigration. The poem itself may have biographical inspiration in Pereleshin's tragic relationship with a younger Chinese man that took place during his Shanghai years as translator, roughly two decades earlier.

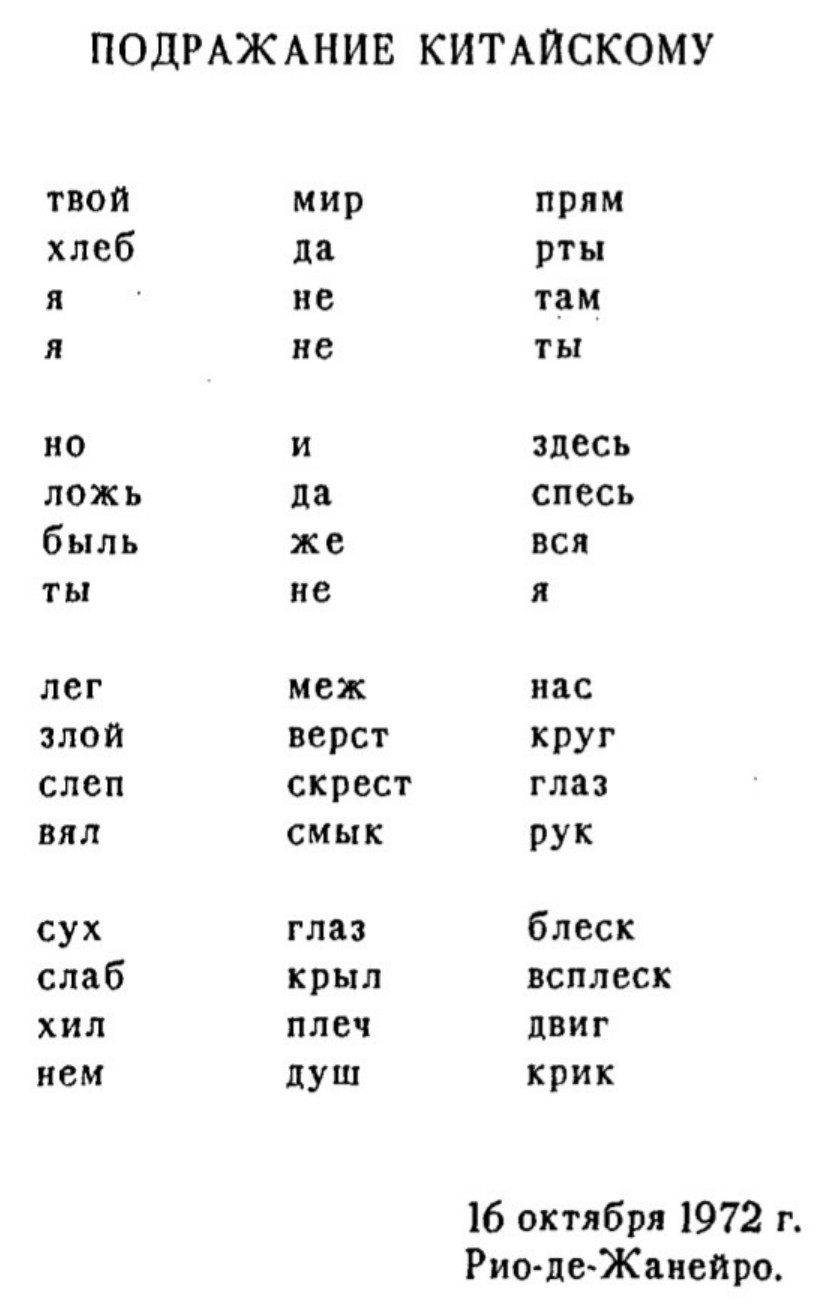

Formally it does not resemble the rest of his poetic output, which is a bit on the conservative side for 20th century verse. Pereleshin was proud of his reputation as "master of the sonnet." He was also perhaps the most accomplished Russian émigré poet to engage with the Chinese poetic tradition, and published several well-received translations in verse. Yet this engagement with Chinese poetry seems to have left little formal trace in his published work. The poem below constitutes a curious exception. Its "imitation" takes place on at least two levels, in layout and in morphology (word-formation). Words are arranged left to right in columns as in most modern editions of Chinese poetry. Each Russian word is monosyllabic, as are characters in Chinese (although strictly speaking words are often formed of more than one chracter); it's worth emphasizing that writing a monosyllabic poem is quite an accomplishment in Russian. These two features seem to be the main loci of imitation, but there may be a third that appears in the second half of the poem as a sly invocation of Chinese regulated verse.

In the spirit of recent attempts to integrate the historiographies of the Eastern and Western emigrations, I have attempted to follow a philosophy of translation that appeared in the Western emigration. This approach remains notorious for its willful disregard of the target language's poetics and aesthetic criteria more generally. For this and any errors I ask the reader's forgiveness.

Your world's straight

Bread and mouths

I'm not there

I'm not you

But right here

Lies and airs

While in truth

You're not me

Lay 'tween us

Leagues' dire arc

Blind cross eyes

Tired clasp hands

Eyes' dry spark

Wings' weak splash

Arms' sick twitch

Souls' mute shriek

The poem was first published in:

Russians in Asia: Literary and Historical Annual. Vol. 1. 1994. p. 15

It was republished in:

сост. ВП Крейд, ОМ Бакич. Русская поэзия Китая: антология. М.: Время, 2000. p. 409-410

For more on Pereleshin, see:

Bakich, Olga. Valerii Pereleshin: The Life of a Silkworm. University of Toronto Press, 2015.