Thomas Gaflan

自己人: A Better America through Chinese Counterstrike

ISSUE 71 | THE FRENCH ISSUE | JAN 2017

In China, the first-person team-based tactical combat game Counterstrike is called CS — a touch easier to pronounce — and it was played seriously and broadly between about 1998 and 2005 in Chinese internet cafes, the typical example of which was a windowless room stuffed with shirtless teen boys, cigarette smoke, and a pervasive sense of fire hazard. Players of Counterstrike are assigned to one of two teams: terrorists or counterterrorists. In Chinese, before a broad cultural interest in terrorism took hold, this translated instead to the jingcha and the tufei, the police and the bandits.

CS lacks a game mode that specifically reflects the contemporary American situation: it’s a team game, so there is no deathmatch mode in which the last player standing wins. There is no mode in which the bandits shoot the police, the police shoot the bandits, the police shoot the innocent, the innocent shoot the bandits, the innocent shoot the innocent, and everybody shoots themselves. You cannot even shoot a child in CS, so it’s hard to make the argument that such a game is an allegory for American life or America’s future. However, there are some qualities of Chinese game servers that might be useful when we think about policing and violence in the United States.

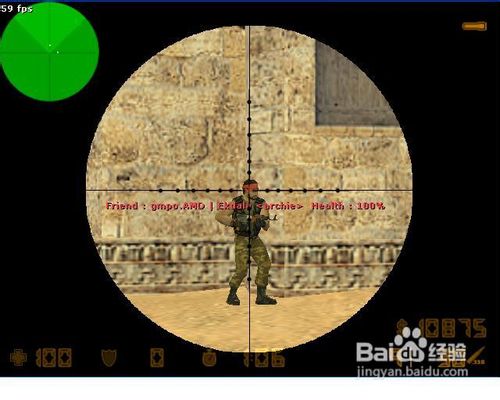

The crucial game setting in CS, the one that determines how any individual round or session will play out, is the way that the game rules treat friendly fire. If you are playing with strangers, and you have friendly fire turned on with no repercussions, you will nearly always have at least one team member who tries to execute one or more teammates during any given game. Games are made up of dozens of rounds; CS teammates appear right next to each other at the beginning of each round, and are expected to immediately buy equipment and guns in order to compete with the enemy, so they make almost helpless targets for their own teammates. It always happens this way, so nobody complains; you fire back, run, or quit the game.

The reasons that friendly fire matches turn into this particular kind of bloodbath are numerous and largely irrelevant. A player is playing poorly, so a teammate takes it upon himself (almost always himself) to mete out punishment at the start of the next round; a player is playing extremely well, and a less accomplished teammate wants to cause frustration until the capable player leaves the game, opening up a space on top of the leaderboard; someone gets bored; someone wants revenge for having gotten shot accidentally or intentionally in a previous round; someone’s money is about to run out on their terminal, and they don’t care whether their team wins or loses the last round; family problems; iconoclasm; simple pique. All of this type of rationalizing would have to be expressed through the game’s chat function, which requires typing, which is impossible to do when everyone’s constantly ducking and shooting each other.

This is, in some American cities, the situation in which both the law-abiding and the criminal find themselves. Because of the immense bias in the criminal justice system, police who kill law-abiding citizens can and often do go completely unpunished. Timothy Loehmann, who killed 12-year old Tamir Rice less than two seconds after arriving on the scene, remains on the Milwaukee police force. The list of legally exonerated murderers is long: Darren Wilson was never indicted for killing Mike Brown; Brad Miller never went to trial for the killing of Christian Taylor; the Baltimore police who killed Freddie Gray were found innocent and are now suing the prosecutor who brought them to trial in the first place. It’s the simplest thing: when there’s no disincentive for shooting someone, you’re more likely to shoot someone. We can see a mirror of the situation in cities like St. Louis, where racist policing means that homicides against black areas are unlikely to be solved, meaning that any criminal is well served by choosing black victims over white ones. Every cycle of violence requires a level of impunity. This takes time to build in the real world, but only about two minutes to appear and flourish in a game of Counterstrike.

In the game, there is also the option to automatically punish friendly fire by a variety of means. People who kill teammates can get their funds reduced (that means they can have to buy less expensive guns in the next round), can be locked out of the game after a certain number of strikes, or can immediately die themselves. None of this ever serves as a deterrent — all it does is ensure that the teamkillers, once they incur the first penalty, will continue to teamkill until they are no longer capable, since they’re less and less competitive, and individual failure is a strong motivator for team shooting. If you get three chances and then you’re banned, then someone who shoots once will almost always shoot three teammates; some line’s been crossed, and in any event, there are other matches to join where one can find a fresh start. There is still a lot of friendly fire in these matches, but it feels counterintuitive, dissonant. People plunked down by the sniper rifles of their teammates curse and wail: the punishment, meted out to accidental misfires just as it is to the intentional assassin, accepts a cost from the community and promises structure in return. The most common thing that people yell out when they come under fire is "自己人!" It literally means self person. Don’t shoot me, I am you! I am part of you.

This phrase is a version of the cry from black communities and others that experience police violence, communities that believe that police are punished for that violence. While Philando Castile bled out in his car after having been shot by the jingcha Jeronimo Yanez, his girlfriend Diamond Reynolds said this: "He don’t deserve this, please. He’s a good man. He works for St. Paul Public Schools. He doesn’t have no records of anything. He’s never been to jail, anything. He’s not a gang member, anything." This is the classic moan of offense: 自己人. For most of his short adult life, Philando Castile cheerfully and capably served meals to children at a public school; between his public service, his taxes, and the thousands of dollars that St. Paul’s exploitative traffic policing had extracted from him in fines, he was worth vastly more in hard currency to the community alive than he was dead, and certainly not worth the trouble and risk of executing. This is why Diamond explained his economic and legal status while trapped in the car with him while he died: even in the absolutely cold logic of self-interest, even if we exclude the humanity of our fellow souls, even if we are treating people like game avatars, no police officer should ever have shot Philando Castile. To the police and the law-abiding community, he was self person.

And yet Philando Castile is dead; and yet the punishments of police, even in the few cases in which they exist, do not seem to matter. Practically nobody plays Counterstrike that’s configured to allow but punish friendly fire. The system asserts the presence of a player who is committed to the game’s outcome, who really wants to beat the other team. It assumes that the player understands the rules and follows no other competing set of rules. To operate correctly, the game requires a kind of person that doesn’t exist. Similarly, American policing and the American criminal justice system are designed in a way that does not understand the daily presence of racism in American society. They assume the presence of an officer who can correctly delineate and identify threats of all kinds, and who will never choose deadly violence in the absence of a real threat. They do not understand that police-citizen relations can be poisoned — or ended — by just a handful of cases.

The only way to play Counterstrike that is any fun is with friendly fire turned off. Your bullets pass through your teammates; you can only actually shoot the people the game intends you to shoot. In one sense, this solution ignores player psychology and player culture, because it doesn’t rely on players to refrain from harming one another; in a deeper sense, this game option wholly understands player psychology and player culture, because it understands that players in the game world tend naturally towards internecine violence.

Imagine a police department designed around the understanding that American police, regardless of who they are or where they come from, are likely to have racist beliefs and habits. Imagine a police department that understands that officers, when given the responsibility to choose whether or not to kill people, will frequently make mistakes, and that those mistakes can threaten public order as much or more as crime does. Imagine a police department that cares less about whether officers have authority, and more about whether they are satisfied that the work they do is worthwhile. Imagine a police department that saw the Stanford Prison Experiment not as material with which to train police officers, but as an argument that the moral and ethical training of police officers can be undone swiftly by shifts in culture and context.

What would this police department do? It would disarm as many individual police officers as possible. When it assigned "non-lethal" countermeasures to police, they would in fact be impossible to use as weapons. It would strictly limit the police ability to harass, humiliate, or intimidate citizens. It would relieve police of the responsibility to make individual decisions about whether or not to harm or kill a person. It would treat police as it treated other citizens, rather than making them hierarchically superior to unempowered "civilians."

The investment required to do these things is admittedly substantial: in order to get them accomplished, citizens themselves would have to begin to disarm, white people and the rich would have to give up the benefits of disparate police attention and protection, police would have to give up pride in their own power, and community resources would have to be spent on experimentation and change. Communities like Milwaukee and St. Louis, who have long used their police forces to violently uphold segregation, will probably never choose to change: the white team shoots everyone wearing the black team’s uniform, and they win every round. But for the rest of us, it’s worth realizing that police violence will never be rare until it begins to be impossible.