Abigail Teller

Shapers of Men

ISSUE 37 | FASHION | FEB 2014

Bracha Asher Yatzar, Blessing for The Fashioner, Who amazingly allows all actions:

Blessed are You G-d our Lord, King of the universe, Who fashioned the man with wisdom, and created within him openings upon openings, hollows upon hollows. It is clear and known before Your Throne of Glory, that if one of them were to rupture, or one of them were to become blocked, it would be impossible to subsist on our own and to stand before You. Blessed are You G-d, Healer of all flesh Who acts wondrously.

Roland Barthes reveals his religious engagement with science when he describes plastic:

So, more than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation; as its everyday name indicates, it is ubiquity made visible. And it is this, in fact. which makes it a miraculous substance: a miracle is always a sudden transformation of nature. Plastic remains impregnated throughout with this wonder: it is less a thing than the trace of a movement. (Mythologies)

How fitting for a substance for transubstantiation!

On Easter 2012, UK Channel 4 announced the completion of Gunther von Hagens’ most conceptually ambitious project to date: a vascular system, compiled from three body donors, nailed to a cross. A G-d image fashioned from creations made in G-d’s image. Jesus Plastinate in a startling attempt to eliminate mystery through the democratization of the divine.

Gunther von Hagens, Jesus, 2012

The Renaissance brought humanism to religious art. Christ, once peaceful and triumphant on the cross, slouches as his body contorts in pain, allowing devotees to relate to and empathize with His suffering. The Christ child softened from a shrunken man into an infantine baby. Flat contours of flesh tones became real bodies, bulbous sacks of skin covering musculature, ligaments, and skeletons. Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo dissected hundreds of corpses in their attempt to attain anatomically accurate representations of man. As the Church holds that humans share a morphological resemblance with G-d, dissection enabled artists to achieve not only the most accurate portrayals of Christ the Son in His human form, but analytically approach an understanding of G-d the Father in His incorporeality. By deconstructing the abject image of a former-man created in the image of the incorruptible past-present-and-future -- G-d, they used human constructs -- religion, science, art -- to construct the divine, while simultaneously displaying their human achievements in the visual arts.

Von Hagens’ attempt at divine likeness is more literal. His process is more destructive than creative. To build his crucifixion, he ruptured and drained the blood vessels of his body donors, injected and clotted their emptied vessels with congealing plastic, burned away their flesh, fat, and bone in acid, and combined what remained of them into a more perfect human form. He explains that he "designed [his crucifixion] to be as real as possible" in order to "[make] religion visible" and "touch the heart." Like Michelangelo and da Vinci before him, von Hagens has attempted to shape the limitless potential that is G-d by mediating it through human developments in the physical sciences and plastic arts.

Von Hagens has stated his ambition to open the first Museum of Man under the futile pretense of showing what man is made of as opposed to what man has made. His museum would serve as a temple both of and for mankind- a place to revive the satisfaction of religious reverence in adoration of the body, the mind, the miracle of their coexistence, and the miracle of their continued existence in a new form of life after death. Bodies excavated before they are ruins, before they are lost to living memory. His subjects attempt to drive off mortality not by looking to G-d, but through human scientific production in tableaux non-vivants that manage a literal interpretation of Barthes' thesis in The Reality Effect, “What is alive cannot signify—and visa versa.”

* * *

After the expulsion, Adam found a name for his companion. He chose Chavah, Eve, “because she was the mother of all lives (chai). And the Lord made for the man and his woman a garment of skin, and clothed them” (Genesis 3:20-21). According to midrash, "His skin was a bright garment, shining like his nails; when he sinned this brightness vanished, and he appeared naked" (Targ. Yer. Gen. iii. 7). Man's boundaries were created as part of G-d’s punishment for his attempt to become godlike. They are required for man to leave the Garden and tend to the world.

The Hebrew word “etzem” means bone. The word is first used in Genesis 2:23 when Adam classifies woman as “etzem mi'atzmi,” “bone from my bone.” Etzem is simultaneously a skeletal structure and an essence. While this may be incongruous in a world where the easiest way for Giuseppe Panza to transport a Donald Judd is to have it re-formed from new materials in its new location and destroy the original, this is not a paradox for the Hebrew language. Exodus 28 describes, in almost reproducible detail, the irreplaceable vestments of the High Priest, Aaron, and his sons. The proceeding chapter explains the procedure for simultaneously sanctifying the new family of priests and their vestments. Once the vestments are sanctified through the ritual, their essence has become sanctified and invests its sanctity on its future wearer. "And the vestments of holiness that are for Aaron will be for his sons after him to anoint through them and to elevate his hands through them. The priest who succeeds him from his sons, who will approach the Tent of Meeting to serve in holiness, will wear them for seven days" (Exodus 29:29-30). The same is true of the sacrifices. The same is true of the altar. Their elevation causes an essential shift in their physical makeup. The burnt remains of a sacrifice are no longer ordinary flesh. An anointed altar can no longer be reduced to a grill. They are now constituted from essentially holy materials that transfer sanctity through contact. While the essence of the Judd's authenticity exists entirely in its concept, the essence of the vestments, sacrifices, and altar exist in their materiality.

Adam calls his companion, “‘etzem from my etzem and flesh from my flesh, this will be called woman because from man it was taken.’ Therefore, man leaves his father and his mother and clings in his wife and they will be one flesh” (Genesis 2:23-24). Humanity is interconnected through its source material. Von Hagens captures the importance of flesh and bone in his plastinates of copulating couples. They have been literally copulati, “fastened together,” through their sex organs. Without their skin, they explode out and into each other. Their muscles are rare red, bursting out, as no boundary contains them within their now limitless bodies. Their flesh and bone has been permanently set together into a singular mass of muscle as they grip each other as if holding on for dear life. They press their faces into their partner’s raw flesh and close their eyes, avoiding the reality of their situation. There is no barrier between them, as their skin has been sensuously stripped from their surfaces, revealing the absence of boundaries in sex and making their passion all the more intense, an expression of the unbounded sex that existed for primordial skinless man in the Garden of Eden.

Stripping flesh is often the first act of destructive formation for von Hagens. Like death, stripping and sex are usually kept private and unseen, even though they, like death, are life-affirming. George Bataille explains,

Stripping naked is the decisive action. Nakedness offers a contrast to self-possession, to discontinuous existence, in other words. It is a state of communication revealing a quest for a possible continuance of being beyond the confines of the self. Bodies open out to a state of continuity through secret channels that give us a feeling of obscenity. Obscenity is our name for the uneasiness which upsets the physical state associated with self-possession, with the possession of a recognized and stable individuality. (Death and Sensuality: A Study of Eroticism and the Taboo)

According to Bataille, this fight against finitude, this desire for the discontinuous, is acted out in human aspirations towards immortality- man’s basic desire and G-d’s greatest fear in the Garden. Our skins record and bind our lives, giving and constructing our selfhood. Without their skins, von Hagens’ copulating figures have lost both their identities and their privacy. They were passively stripped according to their will. This development of “discontinuous existence” occurs between two figures who no longer fear finitude. They have no aspirations, will, ego; no desire. Their acts, which simultaneously illustrate conception and sexual maturation, have no potential outcome. This is heterosexual sex devoid of its basic urge to reproduce. It is the merging of margins between the male and the female in an intensely intimate boundary-less union between two bodies. These bodies have been stripped to fashion a new image rather than to create a new life, illustrating the distinction between the artist and the creator.

Artists act in the realm of shaping, whether they transform pigments and binders into spuriously dimensional images on a flat surface, move objects to transform how we experience space, or simply force us to think. Von Hagens is not the only contemporary artist to become a literal shaper of men. In 1997, Tim Hawkinson fashioned an egg, a bird skeleton, and a feather from his hair and fingernail clippings, painstakingly transubstantiating his detritus from human to aviary. In 1990, Rick Gibson went to court to fight the police confiscation of his freeze dried foetus earrings. Every five years, Marc Quinn molds his blood into refrigerated busts, capturing his essence within his essential life force. Anselm Kiefer masturbated onto books from 1971 to 1991. Artists shape. Artists fashion. Artists are creative. But, like Kiefer's spilt semen, artists do not create.

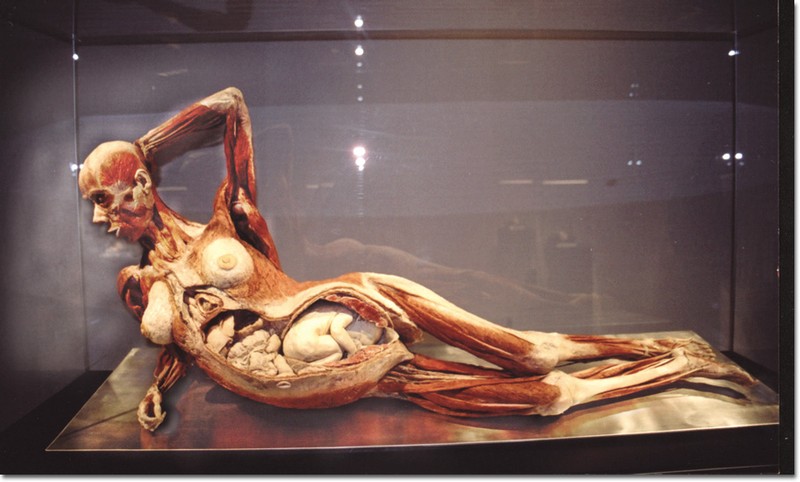

Unless they reproduce. Von Hagens stopped during an interview to admire his Reclining Woman, “Look at this shadow; isn’t this nice… It’s a kind of craftsmanship- in this way, it’s art.” A woman reclines across a pedestal, resting her head delicately on her right arm and her left hand on her head, arching her back to expose what remains of her flesh. She faces down, her eyes closed but her lips slightly pursed, as if choosing to ignore her viewers. Her title emphasizes the ubiquitous odalisque she imitates, rather than the medical condition, her eight month pregnancy, which is the supposed reason for her inclusion in Body Worlds. Reclining Woman has burst with potential; her bulging omphalos, expanded nipples, and widened cervical tract emphasize her margins as she prepares for the new life resting in her ruptured belly.

Gunther von Hagens, Reclining Woman

Much like an inverted fetus, a corpse is a body in process. It grows, shrinks, and decays. Once a skeleton, it is no longer a corpse. It is no longer abject. It is no longer liminal or changing. Von Hagens’ plastinates were once corpses, and will never be skeletons. With the suspension of their natural ability to decompose, these used bodies have lost their potential to promote or create life. They are static, trapped outside, rather than “between the inanimate and the inorganic,” as human intervention has removed them from the Cycle of Life, which, ironically, is the title of one of von Hagens’ Body Worlds exhibitions. This removal from the natural process of life and death has redefined the physical and literal content of the corpse as it is converted and shaped into a flesh and plastic work of art.

These plastinates are actual women who have lost the ability to create; they express the ultimate loss of potential—the never born life, the un-beginning. Hannah Arendt emphasizes the importance of natality when confronting human finitude:

We have seen before that to mortal beings this natural fatality, though it swings in itself and may be eternal, can only spell doom. If it were true that fatality is the inalienable mark of historical process, then it would indeed be equally true that everything done in history is doomed… The lifespan of man running toward death would inevitably carry everything human to ruin and destruction if it were not for the faculty of interpreting it and beginning something new, a faculty which is inherent in action like an ever-present reminder that men, though they must die, are not born in order to die but in order to begin. (The Human Condition)

Von Hagens’ plastinates act out a morbid extension of Arendt’s natality- they show a hope for the future by proving that there is even a beginning in death, reshaping our conception of human finitude. This is the miracle of the Resurrection.

Compare this newness within death to the corpses of world leaders preserved for perpetual display—Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Ho Chi Min, Mao Zedong, Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il—all of whom attempted to displace religion to some degree under their rule. Their skins are saved and their countenances conserved to represent in death what they represented in life; their empty bodies continue to signify who and what they signified when animated. Since these men have not transcended their meaning to become something more in death than they were in life, they have not become works of art. Instead, they have become secular relics deserving of reverence. In electing to donate their bodies to von Hagens, future-plastinates relinquish their identity. They receive an anonymous immortality where they become something new in death that they never were in life.

Von Hagens titled his crucifixion "Jesus." It acknowledges neither Jesus’s divinity nor his future as Christ. Von Hagens has cut Christ from his continuity, freezing him in his own time and space, never to be resurrected. There is no miracle here. Rather than stand as a testament to the attainment of eventual immortality through acceptance of Jesus as Lord and Savior, this crucifixion was fashioned as a testament to von Hagen’s figurative immortality, to the lasting impact of his scientific achievements. “This Jesus will last long after my death and say ‘built by von Hagens.’”